At this point in the Terminology Multifamily Investors Should Know blog series, we’ve gone through over twenty terms. We’ve dove deep into the world of commercial real estate and I trust you’ve learned a ton. In this post, we’ll go a bit deeper and cover the following terms: exit cap rate, 1031 exchange, letter of intent (LOI), purchase and sale agreement (PSA), and private placement memorandum (PPM). While the terms described here and in prior posts are not organized in a particular way, at the end of this blog series I will create an organized glossary page on the JP Acquisitions website which will help compartmentalize everything into a cohesive picture on the world of multifamily. As always, these posts aim to help investors understand the many aspects of multifamily. Having said that, let’s jump in.

Exit Capitalization Rate

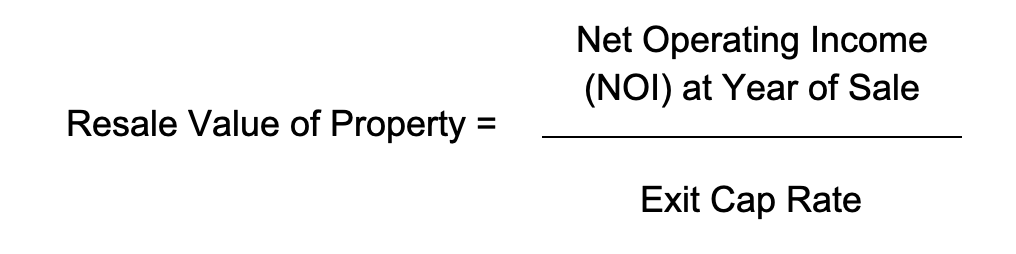

The exit cap rate (also known as the “terminal capitalization rate”) is the cap rate used to estimate the resale value of a property at the end of a holding period. As a side note, the cap rate when the property is first bought is referred to as the “going-in cap rate.” To get the resale value of the property, you take the projected net operating income (NOI) at the year of sale and divide it by the exit cap rate. Exit cap rates are estimated based on similar type projects that have been sold in the market or what is believed to be appropriate for the given area of the property. Coming up with an exit cap rate is part science and part art. On the one end an investor can find similar properties that have been sold in an area to determine an exit cap, but at the same time, it is highly recommended that when underwriting the exit cap the investor takes into consideration possible downside scenarios. In other words, when underwriting we need to be defensible and not simply assume just because a similar property sold for a certain cap rate that our property will sell at the same cap. Thus, it’s a smart idea when underwriting a deal that investors assume the exit cap rate to be 30-50 basis points (one basis point is .01%) above the going-in cap rate. In addition, it’s good practice to stress test the deal by assuming perhaps a 70-100 basis points increase in the exit cap to see if the deal still pencils out. Given that a property is in a strong growing market, interest rates don’t increase too much, and the business plan of that property was executed as planned, typically an investor will notice that the cap upon exit is lower than when the property was bought. Nevertheless, the exit cap rate is one of the most sensitive inputs in an underwriting model. This is true because one small change in the exit cap rate and suddenly a bad deal could look great or vice versa. It’s important to mention that the internal rate of return (IRR) metric is very sensitive to the exit cap rate. Even though the proceeds from sale is the last stream of income in the IRR calculation (and therefore weighted the least due to the time value of money), let’s not forget the proceeds from sale will be the largest cash flow. In other words, if someone assumes too low of an exit cap rate, then the resale value will be inflated which will result in the underwriting model reflecting an unrealistic cash flow distribution once the property is sold. As a result, the IRR will shoot up due to the high resale value. This is the reason why it’s critical that when being presented a deal, an investor should carefully scrutinize the exit cap assumption.

1031 Exchange

In simple terms, a 1031 exchange is the exchange of one real estate property for another which allows capital gains taxes to be deferred. The term gets its name from Section 1031 of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). Before continuing, I want to make it clear that there are many rules surrounding 1031 exchanges that may result in an investor getting partially or fully taxed when trying to perform them. In addition, there are different kinds of 1031 exchanges. Here I will write about the general rules needed to be followed to conduct a 1031 exchange to defer taxes from one investment property to another.

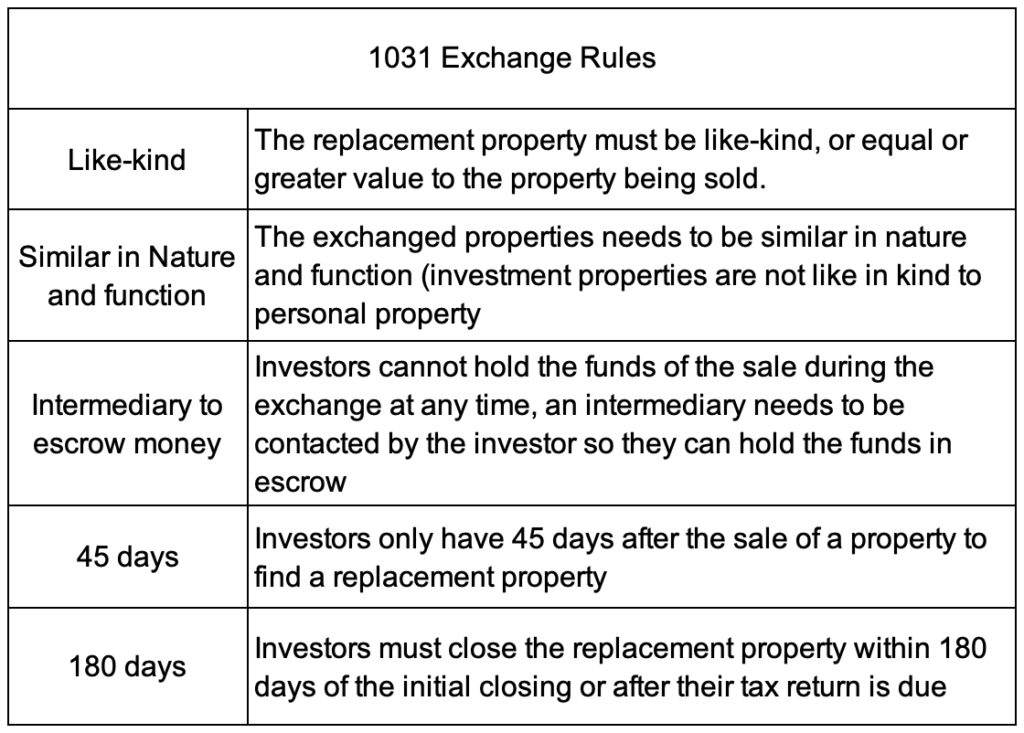

While deferring taxes sounds great, there are many moving parts to take into consideration. Firstly, the replacement property must be like-kind, or equal or greater value to the property being sold. Being like-kind doesn’t necessarily mean the properties must be the same quality or grade and while the SEC is loose with the term “like-kind,” it’s best to talk to a professional for further details. The exchanged properties also need to be similar in nature and function. While properties and personal property (machinery, boats, cars, artwork, aircrafts, personal residence, etc.) qualify for a 1031 exchange, investment properties can never be like-kind or similar in nature to personal property. More so, another rule is that the investor cannot hold the funds of the sale during the exchange at any time, an intermediary needs to be contacted by the investor so they can hold the funds in escrow. Finally, the hardest part of 1031 exchanges and investment real estate properties is that investors only have 45 days after the sale of a property to find a replacement property, and they must close the replacement property within 180 days of the initial closing or after their tax return is due. The table below makes the general rules surrounding 1031 exchanges easier to absorb.

The process of performing a 1031 exchange involves an investor identifying a like-kind replacement property. Then, that investor or group needs to choose a qualified intermediary (also known as an exchange facilitator) to handle the 1031 transaction. It’s important to choose the right qualified intermediary with experience so as to not lose money, miss key deadlines, and end up paying taxes now instead of later. The last step has to do with telling the IRS about the transaction through IRS Form 8824 along with a tax return. That form asks the investor to describe the properties, provide a timeline, explain who was involved in the process, and list the money involved. The bottom line is that 1031 exchanges help real estate investors by allowing them to scale up by buying more profitable properties, deferring capital gains tax, and continuing reinvesting.

Letter of Intent (LOI)

A letter of intent (LOI) is a non-binding document that outlines the terms by which two or more parties intend to later formalize a binding agreement. In simpler terms, an LOI is what a buyer submits to a seller of a multifamily property which outlines under what terms the buyer wants to purchase their property. The LOI avoids wasting the time of all the parties involved because if the LOI isn’t accepted, the process of hiring a lawyer, conducting due diligence, and more is avoided. The terms of the LOI include the purchase price, down payment and loan terms (if you’re using financing), earnest money, conditions/contingencies, broker commission, how long the buyer has to perform due diligence, and more. Usually, the buyer and seller will go back and forth with the LOI and either reach a point to where both parties are in agreement of the terms or perhaps not reach an agreement. Once the letter of intent is signed, the due diligence period starts for the buyer and they will receive access to the property (as stated in the LOI) to perform due diligence. As the due diligence is being done, the seller’s lawyer will draft the purchase and sale agreement (PSA).

Purchase and Sale Agreement (PSA)

The purchase and sale agreement is the document that is written up and signed after a buyer and sale mutually agree on the price and terms of a real estate transaction. This can be thought of as the legally binding version of the letter of intent and once this document is signed, it cannot be broken. The PSA sets forth terms such as the purchase price, financing, closing terms, inspections and surveys, property conditions, and other constraints/contingencies that both parties must abide to. The PSA can take several weeks to finalize and while this document is very long, it’s essential that both parties read the contract to make sure they understand all aspects of the transaction.

Private Placement Memorandum (PPM)

The private placement memorandum is a document drafted by one’s attorney which provides investors with all the information they need about a real estate syndication or fund to make an informed decision as to whether they want to invest or not. The document contains important information such as the operating agreement, investor questionnaires, subscription agreements, risk factors associated with the deal, business plan, projections, sources and uses of the funds, etc. A PPM is used in private transactions when the security (in real estate, the security would be the property) is not required to be registered with the SEC. In other words, the PPM is similar to the prospectus public companies provide when issuing a public offering, however, a PPM is for private transactions.

Conclusion

In this post, we covered yet another five terms: exit cap rate, 1031 exchange, letter of intent, purchase and sale agreement, and private placement memorandum. Given that you’ve read this far through this post and all of the previous four posts, you now have a strong understanding of the many concepts and terms in the realm of multifamily real estate. If you have any questions regarding the terms and concepts in this post or previous ones, don’t hesitate to reach out to either me or someone on our team so we can help explain what is causing the confusion. If you’re interested in investing with us at JP Acquisitions, you can contact us via email, LinkedIn, Instagram, or our investor portal. From there we can schedule a meeting to discuss your investment goals and how our team can be of value. At JP Acquisitions, we’re focused on providing education to those who are eager to learn and that is why we continue releasing educational content each week. This post adds to our company’s history of providing value through informative content, and we hope you enjoyed the read.

Best of luck!

Connect with us!

About the Author

Tedi Nati is the Managing Partner of JP Acquisitions. In his role he is responsible for broker outreach, establishing deal flow, underwriting, marketing, and assisting in the closing process. In addition to his role at JP Acquisitions, he is an Assistant Equity Underwriter at Cinnaire, a non-profit Community Development Financial Institution (CFDI). In his role at Cinnaire, he is responsible for assisting the underwriting team in evaluating and structuring real estate equity investments and assessing the risks and mitigants associated with such. Tedi earned his Bachelor of Science in Finance from DePaul University, where he graduated Summa Cum Laude. In his free time he enjoys reading, writing for his blog (tedinvests.com), looking for multifamily deals, working out, and researching stocks.

Make sure to always do your own research before making any final decisions on buying/investing real estate, stocks, or other securities. I am not a CPA, attorney, insurance, or financial adviser and the information in this blog post shall not be construed as tax, legal, insurance, construction, engineering, health and safety, electrical or financial advice. If stocks or companies are mentioned, I sometimes have an ownership interest in them – DO NOT make buying or selling decisions based on my posts alone. If you need such advice, please contact a qualified CPA, attorney, insurance agent, contractor/electrician/engineer/etc. or financial adviser.

ivermectin 3mg otc – atacand brand carbamazepine over the counter

Your comment is awaiting moderation.