Terminology Multifamily Investors Should Know (Part 3)

November 21, 2022Terminology Multifamily Investors Should Know (Part 5)

December 5, 2022This is part four of the Terminology Multifamily Investors Should Know blog series. In this blog series, we seek to educate multifamily investors on the terminology used in the world of commercial real estate so they can confidently speak on and underwrite multifamily deals. This post will cover the following terms: general & limited partners, return on equity (ROE), return on investment (ROI), equity multiple, capital stack, and bridge loan. In the last post we touched on underwriting, sponsor fees, cash flow waterfall, preferred return, and cash-out refinance. As noted in the other posts, the terms are not organized in a specific way, but once the blog series comes to an end I will create an organized glossary so to provide a more cohesive picture of multifamily real estate. If you haven’t already, I encourage you to read the last three posts which can be found below.

Part one: net operating income (NOI), capitalization rate (cap rate), cash flow, debt service coverage ratio (DSCR), cash-on-cash (CoC)

Part two: equity, debt, appreciation, internal rate of return (IRR), multifamily building classifications

Part three: underwriting, sponsor fees, cash flow waterfall, preferred return, cash-out refinance

General Partners & Limited Partners

There are many ways to invest in real estate and at JP Acquisitions we syndicate deals under Rule 506(b). A syndication is a partnership between multiple individuals that pools resources, capital, and talent to enable the acquisition/purchase of an apartment building. Syndications allow investors to acquire larger properties which might have been difficult if someone were to do it themselves. Syndications are composed of general partners (GPs) and limited partners (LPs). General partners manage the deal while limited partners are the investors. LPs invest in syndications for ownership, returns, and tax benefits and rely upon the general partners to deliver upon the business plan of the syndication. A syndication can be done on various types of real estate such as apartments, mobile home parks, self-storage, senior housing, student housing, developments, etc. While the asset can vary, the principal is the same and that is to invest in a real estate asset through the combined capital of GPs and LPs to deliver a return. With that being said, let’s dive a bit more into what makes a real estate syndication possible.

In 2012, the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Acts (JOBS act) was signed into law. At that point in time the existing Regulation D Rule 506 was split into two sections: 506b and 506c. Rule 506 is a Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulation that allows businesses to raise private capital with securities (such as equity shares) that are exempt from SEC registration. Rule 506 is beloved by real estate syndicators because it allows them to raise an unlimited amount of money, sell securities to an unlimited number of accredited investors, not have to register the security (in this case real estate) with the SEC, and not have to meet any state-specific filing or other requirements. The original rule prior to the JOBS Act, known as Rule 506(b), allows businesses to raise as much capital as they would like from an unlimited number of accredited investors, and up to 35 sophisticated investors. An accredited investor and a sophisticated investor can are defined as the following according to the SEC:

Accredited Investor: Anyone who earned at least $200,000 for the past two years and is expected to have an income of $200,000 in the current year. Investors who do not meet the income requirement but have a net worth of $1 million (excluding their primary residence) are considered accredited investors. For couples to qualify, their income must be at least $300,000 or they meet the same net worth requirement.

Sophisticated Investor: These investors do not meet the income or net worth requirements to be an accredited investor, but have adequate experience and/or knowledge in business, finance, and investments in order to evaluate the risk/reward of an investment.

Under the rules of 506(b), investors can go through a self-certification process that confirms they meet the definition of a sophisticated or accredited investor. What’s important to note is that under rule 506(b), companies or sponsors are not allowed to use any form of marketing to promote their deal offering. In order to comply with this law, the sponsor must prove a subsequent and pre-existing relationship with the investor before they present an investment offering.

The new rule after the JOBS Act, 506(c), allows issuers who are selling securities to generally advertise as long as they make the offerings to accredited investors. If someone is not an accredited investor, they are not eligible to invest in 506(c) syndications. Self-certification is not allowed under rule 506(c) and an issuer must follow steps to verify their investors are accredited at the time they make their investment. From the investor’s standpoint, they must have the issuer review or hire someone to review the investor’s financial information (W-2s, tax returns, brokerage statements, and credit reports).

Return on Equity (ROE) & Return on Investment (ROI)

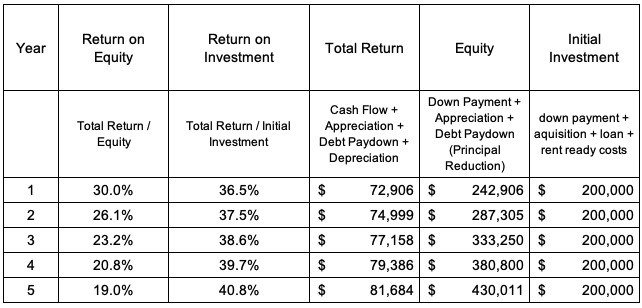

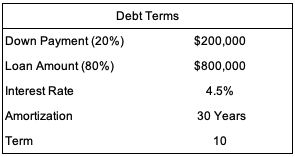

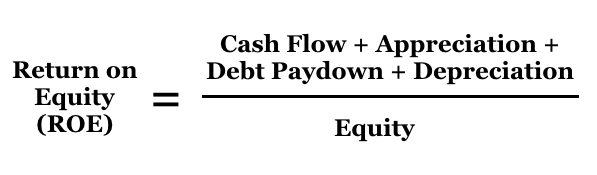

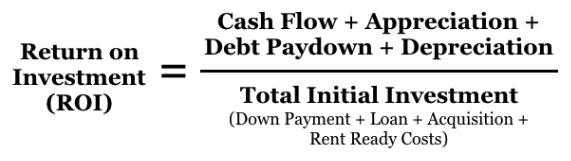

Return on equity (ROE) is a profitability metric used in real estate to measure how much profit is made on an investment property as a percentage of the equity in the property. In order to calculate this metric, you take the yearly cash flow, appreciation of the property, debt paydown, and depreciation and divide it by the equity in the property. Return on investment on the other hand is similar to ROE in the sense that it is a profitability metric, however instead of measuring the profit based on how much equity you have in the deal, it measures profit based on the initial investment. With this knowledge, let’s go over an example. Let’s say an investor buys a $1 million property and puts 20% down (this would be $200,000 and is the initial investment). The investor finances 80% of the property ($800,000) at a 4.5% interest rate with thirty years of amortization for a ten-year term. Yearly the property generates $30,000 in net profit (increasing 2% yearly) and it appreciates by 3% annually. Below I have provided a graphic of the return on equity and return on investment that the investor could expect to receive over the course of five years. Notice how much the ROE and ROI vary from one another. Since the return on investment metric is based only on the initial investment, the denominator of the equation does not change and thus does not take into account principal paydown amongst other factors. Return on equity on the other hand accounts for adjustments in how much equity you have in the deal and as a result is a better way of calculating return over the span of an investment. Something we must remember is that properties don’t always appreciate in value and can also stagnate in value or dare I say depreciate. Also, investors aren’t always able to increase rents as they may have thought at the onset of a real estate investment. Nevertheless, given that you’ve done your homework on the market you choose to invest in, you should see sizable appreciation in your property over the long-term. If you’ve read the previous three posts on multifamily terminology, you now understand the core profitability metrics in real estate: internal rate of return (IRR), cash-on-cash (CoC), return on investment (ROI), and return on equity (ROE).

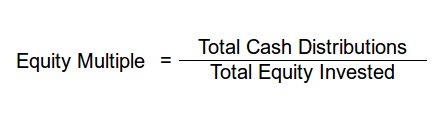

Equity Multiple

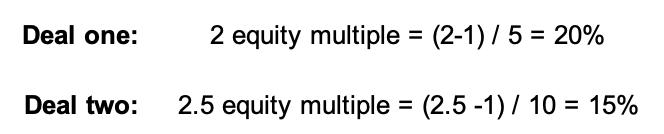

Equity multiple is a return metric used in commercial real estate which measures the total cash distributions received from an investment divided by the total equity invested. For example, if the total amount invested into an apartment property totals $500,000, and the total cash distributions including the sale of the asset equals $1 million, the equity multiple would be 2 ($1,000,000 / $500,000 = 2). If your equity multiple is below one then you will lose money, when it is equal to one you will break even, and anything above one means you will make money on your investment. Equity multiple is a relatively simple return metric compared to others such as IRR, cash-on-cash, or preferred return. While this return metric is simple to understand, it does not factor in the time value of money like the internal rate of return (IRR) formula. The nice thing about the equity multiple is that it can be converted to an annual return figure. In order to turn an equity multiple into an annual return figure you would use the following formula (equity multiple – 1 / years). If we take the above example of the 2 equity multiple and divide it by let’s say a 5-year time period then you would see that your annual return would be 20% (2 -1 / 5 =20%). More so, the equity multiple can be used to value two separate real estate deals once you convert the equity multiple of both deals to annual figures. For example, let’s say that you have two separate real estate deals and deal one has an equity multiple of 2 with a five year hold period while the other has an equity multiple of 2.5 with a ten year hold period. The illustration below shows the annual returns you could expect to receive from both investments. With this concept in mind, you now have another tool in your belt that allows you to quickly measure the potential returns of a multifamily deal.

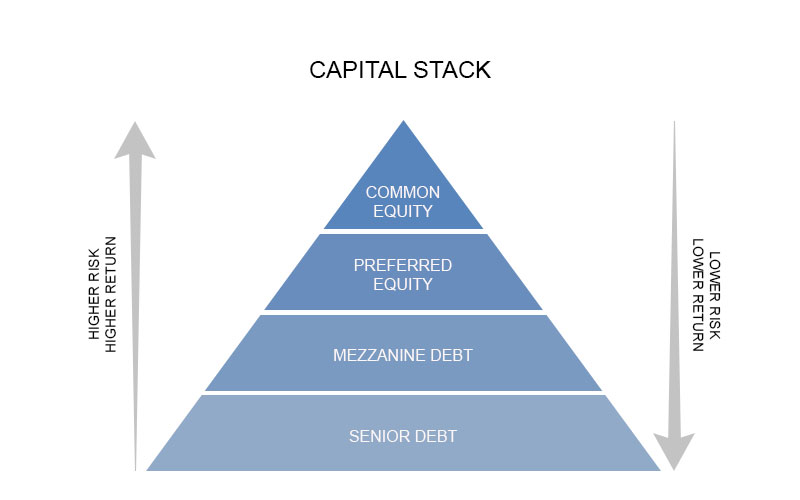

Capital Stack

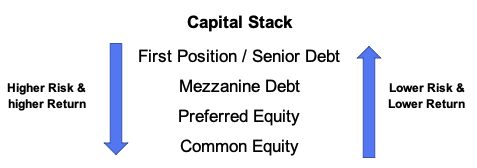

The capital stack refers to the organization of debt and equity used to finance a real estate transaction. Depending on the type of real estate transaction, there can be more or less debt and the types of debt and equity can vary. Capital stacks are often depicted in the shape of a pyramid with the people or entities who would get paid first if the deal is to fall apart at the bottom of the pyramid. The debt at the bottom of the pyramid is in the first position (also called the senior debt). What senior debt means is that if the borrower were to foreclose on the property, the entity or persons in the first position would be paid before anyone else. The senior debt is collateralized via a property lien which is a legal claim on a property that allows the debt issuer to claim the property if the debt cannot be repaid. In multifamily transactions the entity in first position is typically a bank. Sometimes there will be a lender in the second position and that debt is referred to as mezzanine debt (more on this term in a later post). Following mezzanine debt is preferred equity which I touched on in the third post of this blog series. Finally, at the top of the pyramid is the common equity or in other terms the cash that an investor or investors (depending on if the deal is syndicated or done through a joint venture) will put into a deal. I should note that it can be confusing at times when referring to the capital stack as a pyramid since you would expect the debt in first position to be at the top of the pyramid. Thus, I created an alternative illustration of a capital stack (see below) to make this section of the post easier to understand.

What you’ll notice is that the debt at the bottom of the capital stack pyramid (the senior debt) takes on the least amount of risk. This is true because they are repaid first in the event of a default. In addition, since the senior debt is entitled to being repaid first which acts as a sort of safety net, that entity charges the lowest interest rate. The risk increases as you go higher in the capital stack pyramid and therefore the return that those entities or persons require is higher.

Now that you understand what a capital stack is, let’s go through a simple example. Let’s say an investor purchases a property for $1 million and finances the deal with 80% debt and 20% equity. The investor takes out a loan of $800,000 (80% debt) from the bank and that would be what is known as the senior debt. The remaining $200,000 (20% equity and that amount does not include closing costs for simplicity) would be financed via equity (common equity). In this simple case, the capital stack would consist of an $800,000 senior loan and $200,000 in common equity. In other transactions, such as those involving low-income housing tax credits, there are typically multiple sources of debt in which the terms of the order that creditors get paid in the event of a default vary. Thus, in those transactions, the capital stack would consist of a senior loan followed by a series of subordinate loans. Capital stacks can get more complicated depending on how the sponsor of a deal chooses to structure the various levels of debt and equity.

Bridge Loan

A bridge loan is a short-term financing tool used until an investor can secure permanent financing. These types of loans come with interest-only payments which means that the borrower has to cover only monthly interest charges for the entire loan. Once the term of the loan is finished, a balloon payment must be made to pay down the balance. A balloon payment refers to the total lump sum of a loan paid at the end of a loan’s term which is significantly larger than all other payments made until then. Bridge loans can last anywhere between three months to three years and have higher interest rates than fixed-rate loans. These loans are typically used to finance the construction or rehabilitation of a property. For example, let’s say an investor purchases a $1 million property that is severely distressed and needs major rehab work done. The property is not generating income and thus the investor cannot get a traditional fixed-rate loan and therefore opts in for a bridge loan. The total cost of the renovations will be $300,000 and the bank says they’re willing to finance 80% LTC (loan to cost) at 6.5% interest for twelve months. The bank in total will provide $1.04 million (($300,000 + $1,000,000) * 80%)) and the rest is to be financed by the investor. Once the renovations are complete, the investor will lease up the building until it is stabilized (90%+ occupancy) so that the building appraises at a value large enough so that when they take out a traditional fixed rate loan it is large enough to cover the balloon payment of the bridge loan. This is a simplified example of how an investor may use a bridge loan to finance a rehab plan of a property. I should note that some lenders will finance the cost of the property in addition to the rehab/construction budget (this is referred to as loan-to-cost), while others will only be willing to finance the value of the property (loan-to-value). Whether a lender chooses LTC (loan-to-cost) or LTV (loan-to-value) when providing financing options depends on the risk of the business plan. Nevertheless, because there is more risk with bridge loans, the interest rates lenders charge on this type of loan are higher than that of fixed-rate loans. The good news is that while the interest rate may be high, bridge loans tend to close fast and have extension options if needed.

Conclusion

We now find ourselves at the end of yet another post on multifamily terminology. We’ve built on so much and to reiterate in the last post we covered underwriting, sponsor fees, cash flow waterfall, preferred return, and cash-out refinance. I hope you’ve been able to understand the terms that have been touched on so far and in the event something does not make sense, don’t hesitate to reach out to me or someone on the team so we can better explain a term or concept. If you’re interested in investing with us a JP Acquisitions, schedule a meeting with me or someone on our team so can we touch base on your investment goals. We can be reached via email, LinkedIn, Instagram, or our investment portal. I hope you enjoyed this post and look forward to the next one coming out soon!