|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

A multifamily syndication is a structure in which multiple investors pool their equity and resources together in order to purchase a multifamily asset. Syndications typically have two parties involved: the multifamily syndicator (otherwise known as the sponsor or general partner) and passive investors (limited partners). The syndicator is responsible for finding the multifamily opportunity, underwriting the deal, sourcing equity, arranging the financing, and streamlining the transaction process until the deal is closed (if you want to learn more about what syndicators do, read this blog post we wrote). Once the multifamily property has closed, investors (in most cases) will collect passive income from the property and receive a return upon the sale of the asset.

Multifamily syndications may be structured in a number of different ways and that will determine what kind of returns you can expect as a passive investor. In this post, I will outline some common multifamily structures so you can better conceptualize the potential returns of a deal you’re considering investing in. Syndicators outline the structure of a deal in their investment package which is distributed to investors. More so, the structure of the deal is outlined in a PPM (private placement memorandum) which is a document drafted by the syndicator’s attorney which provides investors with all the information they need to know about the syndication or fund to make an informed decision as to whether they want to invest or not. I’ll argue that this post is more for people who have a firm understanding of multifamily syndications already. Nevertheless, let’s jump into some common deal structures of multifamily syndications.

Straight Split

A straight split is one of the most simple multifamily structures to understand. A straight split is when the net cash flow and profits are split between the limited partners (passive investors) and the general partners (the deal sponsor). In a straight split scenario, the limited partners are favored. Here are some common straight splits in multifamily syndications:

- 90% LP / 10% GP

- 80% LP / 20% GP

- 70% LP / 30% GP

- 60% LP / 40% GP

Preferred Return

Many syndications today are structured with a preferred return, also known as a “pref.” A preferred return is a percentage return given to passive investors before the sponsor can receive even a penny. Before going further I want to point out that the sponsor’s share of the profit after the return hurdle has been paid is sometimes referred to as the “promote.” In today’s market, preferred returns range anywhere from 6%-9% in multifamily offerings. Preferred returns are calculated by multiplying the preferred return of a given deal by the total equity put into the deal. An important distinction is that preferred returns can refer to an internal rate of return hurdle or a simple percentage of the capital account.

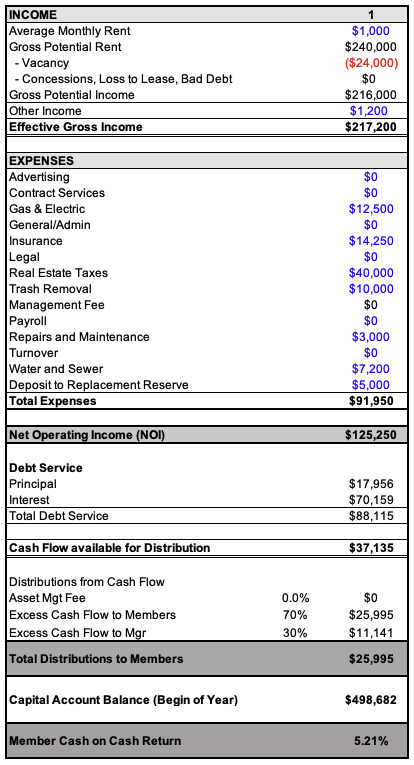

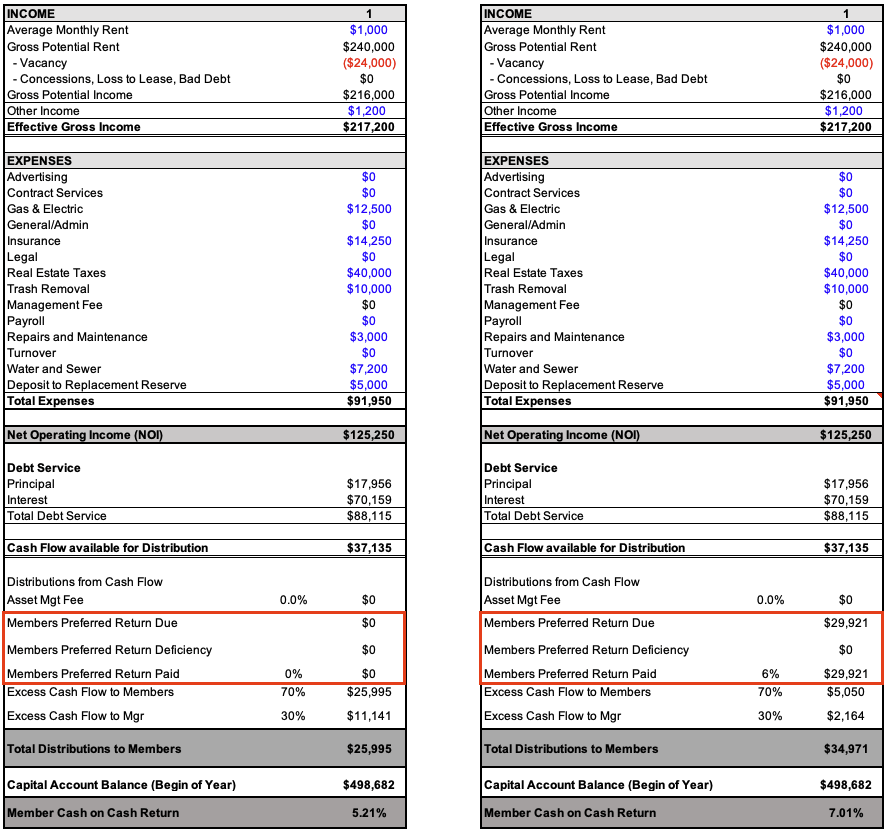

I’ve put a side-by-side scenario of the same deal in the image below. On the left, you can see the straight split structure which I outlined above. On the right is the preferred return structure. As stated before, in the straight split structure after calculating the split the limited partners (referred to as “Members” in the table) received $25,995 while the GPs received $11,141. In the preferred return scenario, the limited partners received a total of $34,921 ($29,291 + $5,050). The return is higher for the limited partners in the pref scenario because they received a 6% return which amounted to $29,921 and the remaining 70/30 split summed up to $5,050. The 6% return was calculated by multiplying 6% by the capital account balance (i.e. the equity put into the deal) and in mathematical terms, it looks like this: 6% * $498,692 = $29,921. You’ll notice that the general partners received a smaller share of the profits in the preferred return scenario because the 6% return had to first be distributed to the limited partners before the general partner could participate in the profit sharing. A nuance that I’ll note is that the pref structure below assumes that the general partners had not put any capital in the deal. Had the general partners put equity in the deal, their equity contribution would be treated the same as the limited partners.

Straight Split

Preferred Return

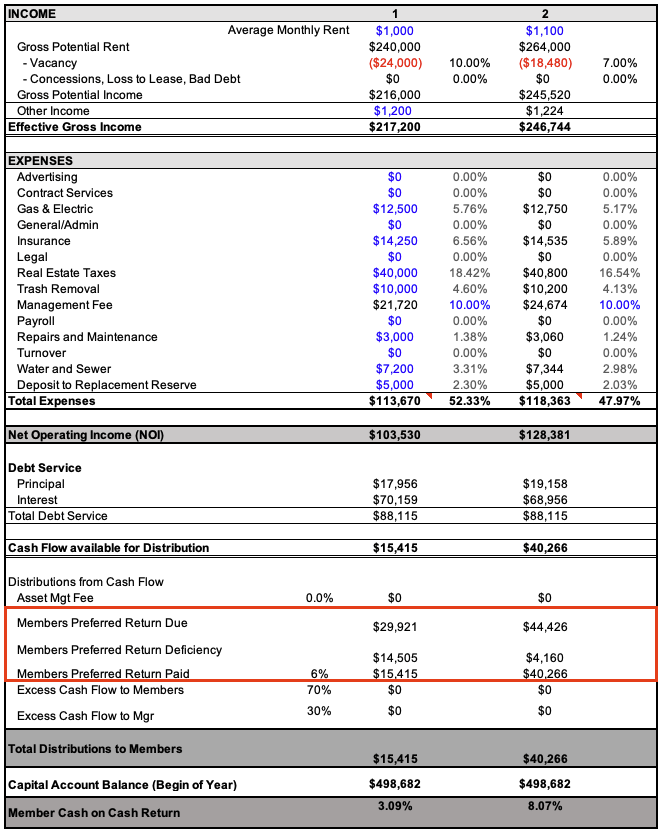

A great aspect of preferred returns is that they accrue. This means that if the sponsor team doesn’t meet the preferred return in one year, they must supplement the next year’s return with what was not paid in the previous year. In the image below, I took the same deal we’ve been working with but artificially boosted the expenses by adding a 10% management fee (calculated by taking 10% of the “effective gross income”). You can see that since the preferred return was not able to be met in year 1 and only $15,415 was paid of the total $29,921 pref, the preferred return accrued to the amount of $14,505 (referred to as “Members preferred Return Deficiency” in the image). The $14,505 shortfall was calculated by the ability of the sponsor team to only be able to pay off $15,415 (the cash flow) of the total $29,921 pref. As a result, in year two the $40,266 available for distribution covered a majority of the shortfall however there still wasn’t enough cash flow to cover all of the pref which resulted in $4,160 to be owed to the limited partners in the following year. If I extended this scenario to year 3 you would have seen the $4,160 be paid off in addition to the pref that was owed and then followed by the remaining cash flow being split 70% to the limited partners and the remaining 30% to the general partners. I’ll note that not all syndications are structured in a way that the pref accrues. Some sponsors incorporate a pref in the deal structure, but it doesn’t accrue, negating the investors’ downside protection. More so, in a pref structure, the general partner is incentivized to make the deal run in the most efficient way possible so they can earn a portion of the profit. In a straight split structure, the sponsor knows they will get paid regardless of how the deal performs so long as there is money available for distribution. The pref structure allows for trust and accountability to be built with the deals sponsorship team (the general partner).

Waterfall Structure

The last structure that we will cover is the most complicated and adds additional hurdles to the waterfall. A “waterfall” (this term is covered in the glossary section of our website) can be thought of as a series of pools in which cash flows to one entity or individual to fill a single pool before spilling over to the next one. In other words, a waterfall is used to describe how limited partners and general partners are repaid through a share of distributions. The preferred return structure is one example of a waterfall structure because the pref ‘pool’ so to speak must be filled prior to any straight split taking place. The waterfall structure is usually based on a type of return hurdle that must be met in order to progress to the next level of the waterfall. There are a variety of waterfalls that can take place and this type of structure is most commonly used when a sponsorship team partners with a sophisticated private equity firm. As more and more layers are added to a waterfall, the structure becomes more complex. An example of a complex multilayered waterfall based on multiple return hurdles is shown below.

- 6% preferred return

- 80/20 split of profits until passive investors (limited partners) receive a 10% internal rate of return (IRR)

- Then, a 70/30 split until investors have reached a 12% IRR

- 50/50 split between limited partners and sponsors

What the IRR return hurdle does is ensure that the limited partners get their initial investment back. Something important to note is that the IRR calculation isn’t positive unless the initial capital of the investors is returned. As a result, this complex waterfall structure incentivizes the sale of the asset or a refinance in which 100% of the capital is returned to investors so that the IRR can become positive. This is true because it takes a lot of capital in order to return the total equity that the investors put into the deal. Cash flow alone almost always will not get you to a positive IRR relatively quickly (less than 5 years) unless the cash flow from the property is incredibly strong (this is unlikely). Furthermore, this structure provides the strongest incentive for the general partners to perform well because of the IRR hurdle. In addition, this structure incentivizes the general partner to put up more capital so that the IRR hurdle can be met quicker. It is likely that as a limited partner you will see the preferred return structure explained in the previous section more often than this complicated waterfall structure. However, it is common as deals get larger that the sponsor incorporates a complex waterfall structure will IRR hurdles, and in those deals because of a large amount of capital required, usually, a sophisticated private equity firm comes into the deal.

Let’s keep things a bit more simple and say that there is an IRR hurdle of 10% with a 50/50 split thereafter. This means that once the investor achieves a 10% IRR on capital invested in the deal in the form of cash distributions, refinance proceeds, and sale proceeds from the project, anything after is a 50/50 split. This would be an example of where investors achieve a solid target of 10% IRR, and the project’s general partners (the sponsorship team) receive a bonus for hitting those return hurdles (i.e. the promote). A nuance to this is that sometimes the preferred return is compounding. What this means is that any shortfall in distributions in one year is then multiplied by the pref percentage and owed in the next year. The compounding preferred return can be complicated to understand and I won’t dive into it but is nonetheless an important aspect to note.

For those of you that want to dive deeper into the weeds, I want to make you aware of a complicated private equity (PE) structure that could take place. This “complicated” PE structure involves a catch-up provision which means that the limited partners receive 100% of distributions until they achieve some preferred return requirement (whether an IRR hurdle or simple pref calculated as a percentage of equity committed to a deal). With a catch-up provision, once the limited partner receives their pref, the general partner receives 100% of excess cash flow until some equitable balance is reached (that balance is usually a percentage of all cash flows received up until that point). For example, imagine a limited partner contributes 100% of the required capital to a real estate deal for a 12% preferred return and 50% of all excess cash flows above that threshold. The catch-up provision states that the limited partner will receive 100% of all cash distributions until they have earned a 12% IRR, at which point the general partner receives 100% of cash distributions until both partners have received 50% of profit distributions. Once the general partners have caught up with the limited partners, both partners receive any remaining cash flow 50/50. This structure with a catch-up provision is unlikely to be seen unless there is a private equity firm investing in the deal at hand.

Conclusion

I trust that the various deal structures I outlined above will help you conceptualize how returns can be distributed in multifamily deals. You should know that deals can be structured in many different ways and it is up to the sponsor team as to how they want to do so. Whether a deal distributes cash flow via a straight split, preferred return, or a complicated waterfall, you now know how the different structures incentivize the sponsor team and change the economics. There have certainly been some complex topics covered in this post and I encourage you to dive deeper for your own knowledge so you’re better equipped to invest in more complicated deals.

If you have any questions regarding the terms and concepts in this post or previous ones, don’t hesitate to reach out to either me (tedi.nati@jpacq.com) or someone on our team so we can help explain what is causing the confusion. If you’re interested in investing with us at JP Acquisitions, you can contact us via email (contact@jpacq.com), LinkedIn, Instagram, or our investor portal to set up a meeting.

As always, I hope you enjoyed reading this post as much as I have writing it. Best of luck!

Connect with us!

Tedi Nati is the Managing Partner of JP Acquisitions. In his role he is responsible for broker outreach, establishing deal flow, underwriting, marketing, and assisting in the closing process. In addition to his role at JP Acquisitions, he is an Assistant Equity Underwriter at Cinnaire, a non-profit Community Development Financial Institution (CFDI). In his role at Cinnaire, he is responsible for assisting the underwriting team in evaluating and structuring real estate equity investments and assessing the risks and mitigants associated with such. Tedi earned his Bachelor of Science in Finance from DePaul University, where he graduated Summa Cum Laude. In his free time he enjoys reading, writing for his blog (tedinvests.com), looking for multifamily deals, working out, and researching stocks.

Вы реально понимаете что происходит в Украине?!

Мне кажется нам подставляют какие то лживые новости и мы часто не читаем статьи из первоисточника https://www.perplexity.ai/.

Перебрав кучу источников наткнулся на сайт, где чувствуется что СМИ дают хоть какую то картину жизни в которой находимся.

Очень важно в современном мире отбирать реальные средства массовой информацииhttps://www.perplexity.ai/ .

Вот еще одна актуальная статья, которая меня задела:

http://kick.gain.tw/viewthread.php?tid=4842909&extra=

http://www.spearboard.com/member.php?u=802473

http://www.oople.com/forums/member.php?u=235259

http://forum.mlotoolkit.com/viewtopic.php?t=3566

http://forum.ll2.ru/member.php?693503-Veronalik

Надеюсь Вам станет полезной.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.