Glossary

Terminology for the multifamily real estate world

Operations & Underwriting

Equity in real estate refers to the value of a building less any debts owed on the property. For example, let’s say that the fair market value of a building is $1,000,000 and I purchase the property for $900,000 from a motivated seller. I finance the property with a 10-year mortgage with 30-year amortization at a 5% interest rate and put down 20%. For now, focus on the down payment and not the other terms I mentioned for simplicity’s sake. The property has an annual appreciation rate of 3% in this scenario and equity is created in a number of ways. Firstly, $100,000 in immediate equity is created ($1,000,000 – $900,000 = $100,000) since I bought the property at below fair market value. The down payment of $180,000 ($900,000 * 20%) also becomes immediate equity. Over 5 years the value of the property increases by $259,274 (($1,000,000*(1.03^5)-$900,000)) which becomes equity. Finally, the number of mortgage payments applied toward the principal also incrementally increases the equity each month until the property is sold.

Investors who purchase wisely and use leverage conservatively and appropriately can more often than not grow equity throughout their holding period. The longer the holding period, the more equity is built up in a property. This is true not only through the principal payments made on a mortgage, but through market appreciation. In addition, an investor could increase their equity on a property through renovations. Going back to the example, if I had chosen to renovate the property through various upgrades (adding new appliances, flooring, etc.) then the fair market value of my property would be higher. I should note that sometimes equity can be negative and that occurs when the value of a property is less than that of the debt owed on a property. For example, if I have an outstanding mortgage on a property that is $1,000,000 and the fair market value of the property is only $950,000, then I would have negative equity of $50,000. Nevertheless, for as long as an investor buys a property in a strong market (characterized by job growth, low crime, increasing household incomes, population growth, etc.), then the odds are that the investor will increase equity in their property and come out with a gain when the building is sold.

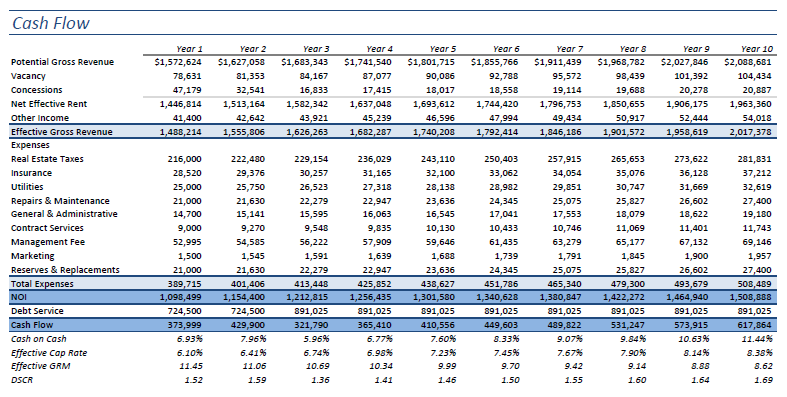

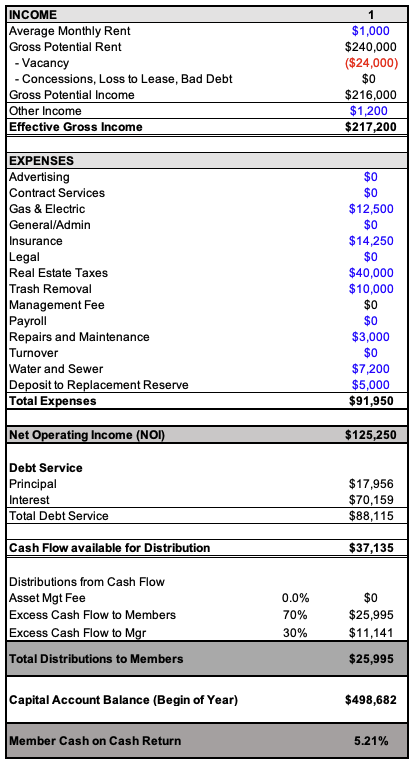

Underwriting refers to analyzing a property’s past and present performance and forecasting future performance to determine the value of that property and understand the associated risks. In other words, underwriting is analyzing, collecting, and organizing a property’s financials to build a projection of income, expenses, and investment returns (a pro forma). The projections are what guide investment decisions, the business plan, and financing options. Below is a picture of a cash flow tab (by “tab” I’m referring to an Excel worksheet) of a financial model to better illustrate what a real estate underwritingmodel looks like. By projecting the income and expenses, we can get an idea of what the property in question will be worth in the future by dividing the future net operating income by the cap rate. In addition, financial models will calculate return metrics such as cash on cash (CoC), IRR,equity multiple, and more depending on the model. In the illustration below, you’ll notice the model calculates cash on cash on the fourth to last line. While you only see one worksheet of the model below, there are many more sheets that allow investors toinput critical factors such as debt terms (down payment, loan amount, interest rate, etc.), expenses, unit mix, etc. I should note that it’s not only real estate investors that underwrite, but also lenders, brokers, developers, and others to various levels of sophistication.

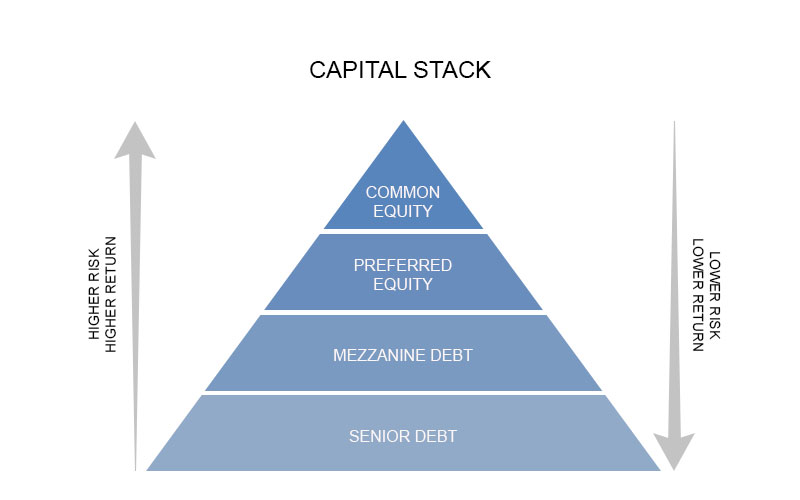

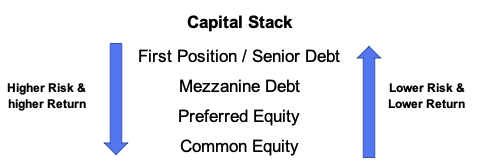

The capital stack refers to the organization of debt and equity used to finance a real estate transaction. Depending on the type of real estate transaction, there can be more or less debt and the types of debt and equity can vary. Capital stacks are often depicted in the shape of a pyramid with the people or entities who would get paid first if the deal is to fall apart at the bottom of the pyramid. The debt at the bottom of the pyramid is in the first position (also called the senior debt). What senior debt means is that if the borrower were to foreclose on the property, the entity or persons in the first position would be paid before anyone else. The senior debt is collateralized via a property lien which is a legal claim on a property that allows the debt issuer to claim the property if the debt cannot be repaid. In multifamily transactions the entity in first position is typically a bank. Sometimes there will be a lender in the second position and that debt is referred to as mezzanine debt. Following mezzanine debt is preferred equity. Finally, at the top of the pyramid is the common equity or in other terms the cash that an investor or investors (depending on if the deal is syndicated or done through a joint venture) will put into a deal. I should note that it can be confusing at times when referring to the capital stack as a pyramid since you would expect the debt in first position to be at the top of the pyramid. Thus, I created an alternative illustration of a capital stack (see below) to make this section easier to understand.

What you’ll notice is that the debt at the bottom of the capital stack pyramid (the senior debt) takes on the least amount of risk. This is true because they are repaid first in the event of a default. In addition, since the senior debt is entitled to be repaid first which acts as a sort of safety net, that entity charges the lowest interest rate. The risk increases as you go higher in the capital stack pyramid and therefore the return that those entities or persons require is higher.

Now that you understand what a capital stack is, let’s go through a simple example. Let’s say an investor purchases a property for $1 million and finances the deal with 80% debt and 20% equity. The investor takes out a loan of $800,000 (80% debt) from the bank and that would be what is known as the senior debt. The remaining $200,000 (20% equity and that amount does not include closing costs for simplicity) would be financed via equity (common equity). In this simple case, the capital stack would consist of an $800,000 senior loan and $200,000 in common equity. In other transactions, such as those involving low-income housing tax credits, there are typically multiple sources of debt in which the terms of the order that creditors get paid in the event of a default vary. Thus, in those transactions, the capital stack would consist of a senior loan followed by a series of subordinate loans. Capital stacks can get more complicated depending on how the sponsor of a deal chooses to structure the various levels of debt and equity.

Net operating income (NOI) tells you how much money you make from a given investment property. NOI is a profitability metric and equals all revenue from a property, minus all operating expenses (OPEX). Operating expenses refer to expenses a property incurs through its normal business operations. OPEX includes line items such as payroll, insurance, taxes, marketing, property management fees (ranges from 3-10% depending on size), utilities, etc. NOI consists of rent collected as well as additional income such as that coming from laundry machines, pet fees, parking fees, etc. NOI excludes not only mortgage payments, but also interest on mortgage payments, taxes, and capital expenditures. It’s important to remember that when evaluating the strength of an investment, projected rents could prove to be inaccurate so it’s important to evaluate the feasibility of rent projections. For example, someone may think they could bump rents up by $100 two years into an investment, but that may prove to be false if that individual didn’t accurately evaluate market rents. The NOI metric is used solely to judge a building’s ability to generate revenue and profit. In the case an investor is taking advantage of financing options, it tells you if a specific investment will generate enough income to make mortgage payments. For example, if a property’s NOI is $50,000 and mortgage payments are $25,000, then you know you’ll have $25,000 pre-tax profit. I mention this term first because we will be using it when calculating the next term, capitalization rate.

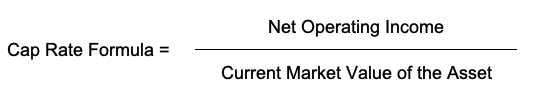

The capitalization rate (also known as cap rate) is used in the realm of commercial real estate to indicate the rate of return that is expected to be generated on a real estate investment property without factoring in financing. For example, if a building has a 5% cap rate and you paid all cash then you can assume you will generate a 5% return on a yearly basis. However, after factoring in financing that 5% return would be lower because you would have to pay the bank principal and interest payments. This metric can be calculated by dividing the income produced from a property (NOI) by the price of a property. For example, if a property has a $1,000,000 purchase price and generates $50,000 in NOI then the cap rate would be 5% ($50,000/$1,000,000 = 5%). While this metric can be useful for comparing the relative value of similar properties in a market, it should not be used as the sole indicator of an investment’s strength because it does not account for leverage/financing, the time value of money, and future cash flows among other factors. Thus, in other terms, this metric indicates a property’s intrinsic, natural, and unlevered rate of return. Something to note is that since cap rates are based on the projected estimates of future income, they are subject to a large degree of variance/change. What this metric also indicates is the time it will take to recover the invested amount in a property. For instance, a property with a cap rate of 10% will take roughly 10 years to recover the amount invested. Hotter markets (those areas with high levels of population growth, job growth, etc.) typically have lower cap rates which means properties are valued higher and vice versa for less desirable markets. While intuitively it may seem that a higher cap rate is better since the return is higher, that is not necessarily true because an investor must factor in individual market factors (crime, access to transportation, job availability, etc.). Cap rates can be misleading in the ways that I’ve noted above and also when evaluating properties with unstable cash flows. The capitalization rate is only useful to the extent that a property’s income will remain stable over the long term. It does not take into account future risk such as depreciation or fluctuations in the rental market that could cause income to change. Nevertheless, using this knowledge you can better get a gauge of not only an investment’s strength, but also understand the market in which you are looking to invest in.

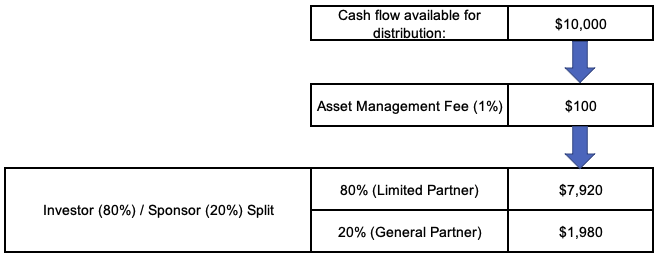

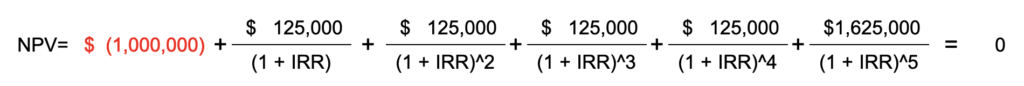

In a real estate syndication structure, cash distributions are calculated and made via what is known as a ‘cash flow waterfall’. A cash flow waterfall can be thought of as a series of pools in which cash flows to one entity or individual to fill a single pool before spilling over to the next one. In the example below, there is $10,000 in cash flow after expenses and debt are paid for. Of that $10,000, $100 must go to the sponsor in the form of an asset management fee (assuming the deal was structured that way). The remaining $9,900 is then split among investors (limited partners) and the sponsor group (general partners) with the cash flowing 80% to the LPs and 20% to the GPs. This example is quite simplified as often the structure of syndications is more complicated. Nevertheless, this gives a general idea of what a cash flow waterfall is. Something that I want to mention is that the sponsor group will almost always take a percentage of the cash flow via a GP/LP split. The split shown in the illustration below is a common 80/20 split and you can see that after the asset management fee is paid, $7,920 (80%) of the cash flow goes to investors and $1,980 (20%) goes to the sponsor group.

As a result of a syndicator putting together a transaction and executing the business plan, the sponsor (synonymous with syndicator) is compensated via a set of fees. Not all syndicators structure their deals the same and depending on the structure, the interests of investors and syndicators could be in conflict. Below I’ve outlined the standard fee structure and benchmark rates that syndicators typically charge.

Acquisition Fee (1-2%): This fee is a percentage of the purchase price and is paid out via the capital raised for a deal. For example, if I’m the syndicator and charge a 1% acquisition fee for a $1M deal, I’ll take home $10,000 (1% * $1,000,000 = $10,000) at closing.

Asset Management Fee (1-2%): The asset management fee is a percent of the gross income (typically) that is given to the sponsor. Normally this fee sits at the top of the cash flow waterfall which means that the sponsor collects this fee before the investors get paid.

Refinance Fee (0.5 – 2%): This fee is calculated by taking a percentage of the refinanced loan amount and it rewards the sponsor for going through the refinance process.

Disposition Fee (1-2%): This fee is associated with the sale of a property and can be calculated by multiplying the sale price by the fee percentage charged by the sponsor.

What’s important to remember is that these fees can be structured in any number of ways. Investors should look into the fee structure of a deal they’re considering investing in so as to make sure their interests are aligned with the sponsor. I’ve seen an acquisition fee be as high as 5% and keep in mind that the acquisition fee comes out of money that is raised, which means your equity in the deal is diluted or in other words you own less of the deal. On a related note, the best way to know if the sponsor’s interests are aligned with that of investors is to see if they have skin in the game. By “skin in the game” I mean that the sponsor group has contributed a fair amount of capital alongside investors (relative to their net worth) into the deal. When sponsors invest their capital alongside investors, you can rest assured that they want to see the deal succeed as much as you do. At JP Acquisitions our team always invests alongside our investors not only because we believe in the strength of our deals, but because we want to align our interests with our investors.

Multifamily investing can be broken down into four distinct building classes: class A, B, C, and D. It’s important that you have the ability to distinguish between the four building classes so as to enable you to determine which asset class best fits your investment objectives. With that being said, the lower you go down the class scale, the higher the cap rate gets and the reasons for why an investor chooses to buy the building changes.

Class A properties are the crème de la crème of multifamily assets. These properties are usually less than 10 years old and are luxury apartments. Class A properties are located in desirable geographic areas and the tenant base in these apartments typically consists of white-collar workers who usually rent by choice. Due to the location of these properties in addition to all of the amenities they offer (fitness center, business center, pool, rooftop lounge areas, etc.) the average rent is high. Class A properties generally have the highest valuation per door and the lowest market cap rates which means they’re usually purchased for appreciation.

Class B buildings are one step down from class A. These apartments can be 10 to 25 years old and are generally well-maintained. The tenant base includes both white and blue collar workers with some tenants renting by choice while the others by necessity. The cap rate for this building type is higher then that of class A. While class B apartments are primarily bought for appreciation, they generally have more cash flow than class A properties. The amenities in class B apartments are less impressive than that of class A buildings, however they normally offer some amenities that are enjoyable for the tenants.

Going further down the scale, C class apartments are typically built within the last 30 to 40 years and are comprised of blue collar and low-to-moderate income tenants. The tenants in class C apartments are usually renters “for life,” yet some of the tenants who are just starting out are likely to work their way up to nicer apartments as they progress in their careers. Rents for this asset type are lower than that of class A and B apartments due to the build, amenities offered, area, and other factors. These deals are attractive to cash flow investors and have higher cap rates than that of class A and B buildings. Many syndicators look for opportunities to turn class C apartments to class B apartments through renovations because they offer tremendous upside. At JP Acquisitions we look for class C properties which require the least amount of work to renovate in order to turn them into class B properties. We’ve found that this strategy of renovating class C buildings tends to yield the highest returns for investors, but opportunities to implement the strategy are far and few between in the markets we’ve studied due to demand.

Class D properties are the lowest on the class scale and are usually built more than 40 years ago. These properties typically house section 8 government subsidized tenants and are located in lower socioeconomic areas. While these properties have the highest cap rates of any property type, there are a number of factors to be aware of. Class D apartments tend to experience higher vacancies, substantial deferred maintenance, and are located in high crime areas. More so, they can require intense management and heavy security. Investors normally shy away from these properties due to the reasons listed. For seasoned investors who have a strong sense of the market in which they invest in, these deals are attractive due to the high cash flow.

In simple terms, a 1031 exchange is the exchange of one real estate property for another which allows capital gains taxes to be deferred. The term gets its name from Section 1031 of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). Before continuing, I want to make it clear that there are many rules surrounding 1031 exchanges that may result in an investor getting partially or fully taxed when trying to perform them. In addition, there are different kinds of 1031 exchanges. Here you’ll find the general rules needed to be followed to conduct a 1031 exchange to defer taxes from one investment property to another.

While deferring taxes sounds great, there are many moving parts to take into consideration. Firstly, the replacement property must be like-kind, or equal or greater value to the property being sold. Being like-kind doesn’t necessarily mean the properties must be the same quality or grade and while the SEC is loose with the term “like-kind,” it’s best to talk to a professional for further details. The exchanged properties also need to be similar in nature and function. While properties and personal property (machinery, boats, cars, artwork, aircrafts, personal residence, etc.) qualify for a 1031 exchange, investment properties can never be like-kind or similar in nature to personal property. More so, another rule is that the investor cannot hold the funds of the sale during the exchange at any time, an intermediary needs to be contacted by the investor so they can hold the funds in escrow. Finally, the hardest part of 1031 exchanges and investment real estate properties is that investors only have 45 days after the sale of a property to find a replacement property, and they must close the replacement property within 180 days of the initial closing or after their tax return is due.

The process of performing a 1031 exchange involves an investor identifying a like-kind replacement property. Then, that investor or group needs to choose a qualified intermediary (also known as an exchange facilitator) to handle the 1031 transaction. It’s important to choose the right qualified intermediary with experience so as to not lose money, miss key deadlines, and end up paying taxes now instead of later. The last step has to do with telling the IRS about the transaction through IRS Form 8824 along with a tax return. That form asks the investor to describe the properties, provide a timeline, explain who was involved in the process, and list the money involved. The bottom line is that 1031 exchanges help real estate investors by allowing them to scale up by buying more profitable properties, deferring capital gains tax, and continuing reinvesting.

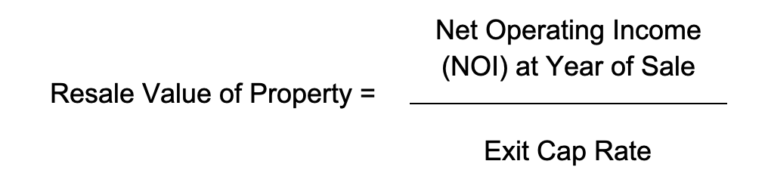

The exit cap rate (also known as the “terminal capitalization rate”) is the cap rate used to estimate the resale value of a property at the end of a holding period. As a side note, the cap rate when the property is first bought is referred to as the “going-in cap rate.” To get the resale value of the property, you take the projected net operating income (NOI) at the year of sale and divide it by the exit cap rate. Exit cap rates are estimated based on similar type projects that have been sold in the market or what is believed to be appropriate for the given area of the property. Coming up with an exit cap rate is part science and part art. On the one end an investor can find similar properties that have been sold in an area to determine an exit cap, but at the same time, it is highly recommended that when underwriting the exit cap the investor takes into consideration possible downside scenarios. In other words, when underwriting we need to be defensible and not simply assume just because a similar property sold for a certain cap rate that our property will sell at the same cap. Thus, it’s a smart idea when underwriting a deal that investors assume the exit cap rate to be 30-50 basis points (one basis point is .01%) above the going-in cap rate. In addition, it’s good practice to stress test the deal by assuming perhaps a 70-100 basis points increase in the exit cap to see if the deal still pencils out. Given that a property is in a strong growing market, interest rates don’t increase too much, and the business plan of that property was executed as planned, typically an investor will notice that the cap upon exit is lower than when the property was bought. Nevertheless, the exit cap rate is one of the most sensitive inputs in an underwriting model. This is true because one small change in the exit cap rate and suddenly a bad deal could look great or vice versa. It’s important to mention that the internal rate of return (IRR) metric is very sensitive to the exit cap rate. Even though the proceeds from sale is the last stream of income in the IRR calculation (and therefore weighted the least due to the time value of money), let’s not forget the proceeds from sale will be the largest cash flow. In other words, if someone assumes too low of an exit cap rate, then the resale value will be inflated which will result in the underwriting model reflecting an unrealistic cash flow distribution once the property is sold. As a result, the IRR will shoot up due to the high resale value. This is the reason why it’s critical that when being presented a deal, an investor should carefully scrutinize the exit cap assumption.

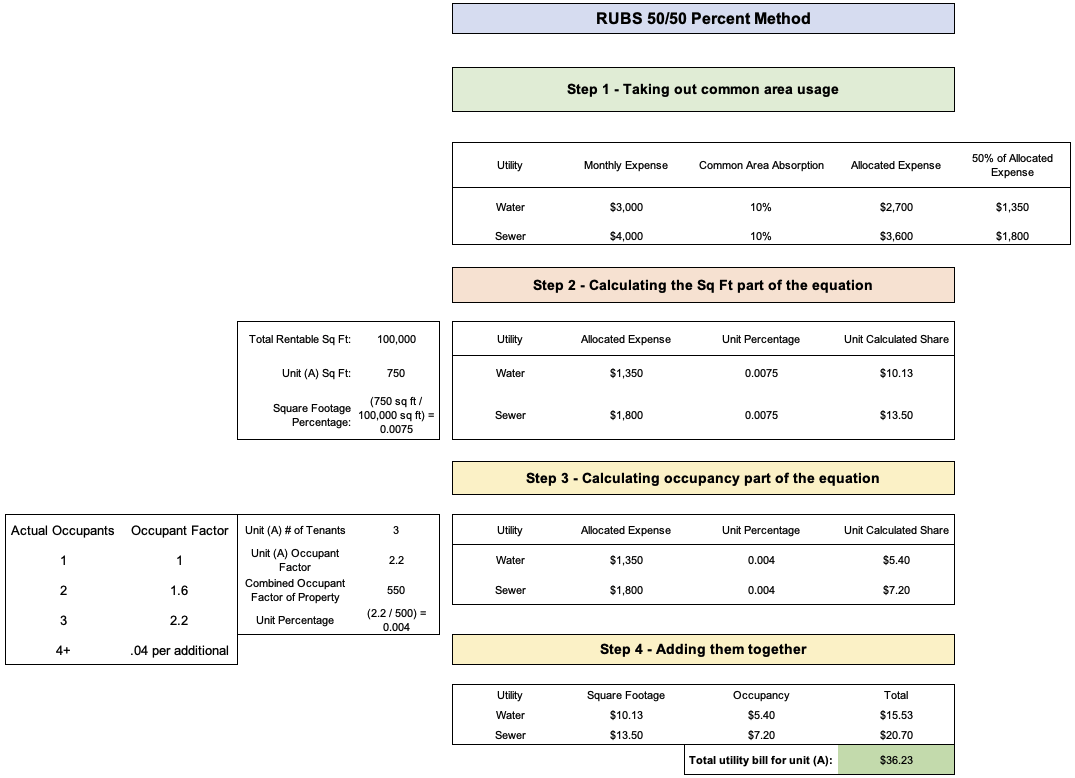

In many older multifamily properties, units are not individually metered, making it hard for landlords to charge back tenants based on their usage. While individually metering each unit is an option, it may come with an unjustifiable price tag. A solution to that is to implement the ratio utility billing system (RUBS) which allows for a landlord to determine a tenant’s utility bill based on factors such as unit square feet, number of people living in the unit, number of bedrooms and bathrooms, and number of water fixtures. RUBS is essentially a way for landlords to reduce their utility expenses all the while increasing rent.

There are a number of ways to calculate RUBS and the calculation below shows the 50/50 split method. This way of calculating RUBS takes into consideration the occupancy as well as the square footage of a unit. Below is a step-by-step illustration of the example outlined here for better comprehension.

Let’s say that an investor buys an apartment building and wants to calculate the amount of increase in rent that will cover the utility expenses for water and sewer for one unit type. The monthly expenses for water and sewer are $3,000 and $4,000 respectively. The investor takes out 10% of those expenses to account for the common area and then splits the remaining expenses by 50% (step 1). The investor then takes the square feet of the unit types (in this case we only have one type) and divides it by the total rentable square feet to get a square footage percentage. That percentage is then multiplied by the allocated water and sewer expense to get the unit calculated share (step 2). The investor must then calculate the occupancy portion of the equation by creating an occupant factor based on actual occupants and dividing it by the total combined occupant factor of the property. The result is the unit percentage which then needs to be multiplied by the allocated water and sewer expense to get the unit calculated share (step 3). Finally, the investor adds the square footage number for both expenses and adds it to the occupancy portion of the equation to get the total utility bill for the unit type (step 4).

With the final bill for the unit type we got in this example ($36.23), the investor would add that amount to the tenant’s rent and notify them that they are being billed for utilities. If the number of people living in their unit was to change at any point in time, their utility expense would fluctuate based on the new number of people living in that unit.

Return Metrics &

Deal Structures

In real estate, the term appreciation refers to the increase in the value of a property over time. There are two ways in which your property can increase in value, through forced appreciation or through macro factors. Forced appreciation occurs when a real estate investor actively seeks to increase the value of a property by increasing rents, identifying additional ways to generate income, reducing expenses, or a combination of the three. Rents can be increased by simply bringing them up to market (assuming they were not there before) or by implementing renovations so as to make the units more attractive, which in turn will make them more desirable so as to command a higher rent. From a macro level, appreciation may result from inflation, increased job opportunities in the market, overall development in the area, or a combination of the three. I should note that appreciation can be a result of inflation because historically rents have increased at the same rate as inflation. Market factors can increase property values as well because as an area becomes more desirable due to a number of factors (increased jobs, population growth, developments in the area), landlords will increase rents. What’s important to remember is that higher rents increase the value of a property because increasing rents translates to higher income. The more income a property makes, the higher valuation that it commands.

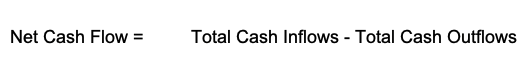

Cash flow is similar to net operating income (NOI), however it’s slightly different. While NOI is simply income minus operating expenditures (opex), cash flow takes into consideration debt payments, depreciation, taxes, etc. Thus, cash flow can be thought of as what is left after all expenses are paid. Real estate investments can generate positive or negative cash flow. When a property has positive cash flow its income exceeds all expenses while negative cash flow is the opposite. Positive cash flow is the goal for real estate investors because it means they’re making money on a property or properties owned. The wider the profit margin, the better the return on investment. Cash flow is the factor used in calculating the internal rate of return metric (IRR) metric which can be often found in pitch decks to investors. I won’t go much further into defining this term because much of what is factored into calculating cash flow I covered when I wrote about NOI. What’s important to remember here is that cash flow factors in all expenses (operating expenditures, debt service payments, depreciation, and taxes) as opposed to simply factoring in opex in the NOI calculation.

The Cash-on-cash (CoC) metric, sometimes referred to as cash yield, is a rate of return often used in real estate transactions that calculates the cash income earned on the cash invested in a property. In other words, CoC return measures the amount of cash flow relative to the amount of cash invested in a property investment and is calculated on a pre-tax basis. The cash-on-cash return metric measures only the return for the current period, typically one year, rather than the return over the life of an investment or project. This metric is calculated by taking the annual before tax cash flow and dividing it by the total cash invested. For example, if a property generates $26,000 in cash flow and the total amount invested is $260,000, then the cash-on-cash return would be 10% ($26,000/$260,000). CoC is considered relatively easy to understand and is one of the most important real estate return on investment (ROI) calculations. I should note, cash-on-cash can be used as a forecasting tool to set a return target. Calculations based on the standard return on investment (ROI) metric take into account total return while CoC on the other hand only measures the return on the actual cash invested, which provides a more accurate analysis of an investment’s performance. The cash-on-cash metric provides operators and investors with an analysis of the business plan for a property and the potential cash distributions over the life of an investment. Below you will see an image that highlights how to calculate the cash-on-cash (CoC) metric for a deal. The numbers used are arbitrary and will change depending on the deal at hand. The words highlighted in blue express that they are used in the calculation to come up with the calculated percentage at the bottom. As a side note, the metric is always calculated as a percentage.

Yield on cost is a financial metric used in real estate to measure the return on an investment based on the initial cost of acquiring a property. To calculate the YoC metric, you need to know three variables:

- Net Operating Income (NOI)

- Purchase Price (including closing costs)

- Capital Expenditure Budget

Below you will see an image that highlights how to calculate the yield-on-cost (YoC) metric for a deal. The numbers used are arbitrary and will change depending on the deal at hand. The words highlighted in blue express that they are used in the calculation to come up with the calculated percentage at the bottom. As a side note, the metric is always calculated as a percentage.

Internal rate of return (IRR) is the most popular method used for identifying the return from a real estate investment. When considering an investment in a multifamily property the question that you must ask yourself is, “If I invest in this property, what is the return I can expect?” IRR is designed to measure the compounded annual rate of return an investor can expect on their investment. IRR can also be thought of as the rate earned on each dollar invested for the time period it is invested in. The part of the definition that is important to focus on is “the time period it is invested in.” The time component of the IRR calculation cannot be ignored because it accounts for the compounding of returns. Mathematically speaking, IRR is the rate of return that sets the net present value of all future cash flows (positive or negative) equal to zero. To reiterate in more simple terms, IRR is a metric that tells investors the average return they have realized or can expect to realize from a real estate investment over time (expressed as a percentage).

The beauty of the IRR calculation is that it accounts for profit and time in a single metric. While the concept of profit is relatively straightforward and can be defined as how much cash an investment generates, the time component in the IRR calculation is more nuanced. When I say “time component,” I’m referring to the time value of money. The idea behind the time value of money is that since inflation affects the value of money over time, a dollar today is worth more than a dollar in the future. For example, $1 today may only have $0.90 of buying power in 3 years due to inflation. In addition, since a dollar will be worth less in the future, each investment has a trade-off or otherwise known as opportunity cost. The idea of opportunity cost can be thought of as what an investor misses out on when choosing one alternative investment over another. What IRR allows investors to do is measure potential returns for various opportunities through one calculation all the while factoring in time. Thus, the IRR calculation provides the opportunity to value the potential returns for multiple investments which have different timelines. However, the calculation works best when looking at investments of the same time period.

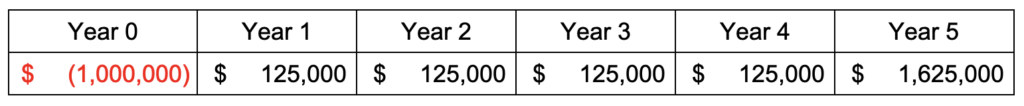

Looking at the IRR calculation may give you flashbacks to the anxiety you had during high school calculus, but if you can understand this formula then you’re one step closer to being able to value potential real estate investments. The good news is that you can use the XIRR function in excel to do the hard work for you. Nevertheless, let’s look at a simple example to better illustrate the concept of IRR.

Let’s say that you buy a property for $1 million. Yearly you’ll earn $125,000 from rental income over four years. You plan to sell the property in five years for $1.5 million. Given these assumptions, set the net present value (link to definition) to zero to determine the IRR. You’ll notice that year 5 has increased cash flows due to the profit from sale in addition to the rental income. The result of the formula is an IRR of 19.31%. Below you’ll see the cash flow schedule in addition to the formula laid out to provide a visual representation.

While the IRR formula gives investors a prediction of what return they can expect on a property, IRR can be difficult to calculate without the right tools and because there is a lot of guesswork in terms of cash flows and sale price. Few investments go exactly as planned and therefore the IRR that an investor predicts at the onset of a project will more than likely change as time goes on. In addition, since IRR takes into consideration the time value of money, if an investor is using yearly cash flow as opposed to monthly cash flow or vice versa for the calculation they will end up with two different numbers. I recommend calculating IRR based on monthly cash flows to get a more accurate picture of what the returns of a deal will look like.

In real estate, a preferred return (also known as a ‘pref’ or preferred equity) is a percentage of profits that an investor is entitled to before the sponsor can receive profit. A typical preferred return ranges between 6% and 9% depending on the investment’s risk. A pref essentially puts the investors first in line to receive returns when it comes time to make distributions. To calculate a preferred return, you multiply whatever the pref is by the total capital raised. For example, if $1M is raised and the preferred return is 6%, then the annual preferred return would be $60,000.

Investors like preferred returns because they know they can assume a certain percentage return as opposed to a regular 80/20 split in which returns vary. With this structure, the syndicator is incentivized to make the property produce as high of a return as possible since they know they will not get paid if they don’t meet the preferred return hurdle. In the event that the preferred return cannot be payed, most syndicators structure the deal so that the pref accrues. For example, If a syndicator structures a deal with an 8% preferred return and cannot pay the full amount, then the remainder that was not paid is carried over into the next year. If upon sale there is any outstanding balance that is owed to investors as a result of the preferred return, that must be paid before the syndicator can receive their share of profit. Many syndicators structure their deals with a compounding factor on top of the preferred return in the event that it cannot be paid. What that means is that if the preferred return was not totally paid in that year, the syndicator will pay back the pref in addition to a percentage they promise. For example, If a syndicator cannot pay a preferred return of 8%, the residual of what they did not pay will carry over to the next year in addition to 3% of the balance that was carried over. The compounding preferred return is a favorable syndication structure because it incentivizes syndicators even further then the standard preferred return.

Below is an illustration of how the previous cash flow waterfall would change with a preferred return structure. Notice how the total return to investors changed from $7,920 in the waterfall under “Cash Flow Water” to $9,520 ($8,000 + $1,520) in this example. As I stated before, since the preferred return acts as a hurdle before the syndicator can get paid, the syndicator is incentivized to make the project perform better so they can receive a higher return. Assuming the pref accrues, this pref structure is a win-win scenario for the investor since no matter what they get their return. Nevertheless, just because a syndicator provides investors with a pref that doesn’t necessarily mean the deal is a strong investment. The deal still stands to face the risks associated with multifamily real estate such as the inability to make debt payments, an increase in interest rates resulting in a lower valuation, and more. It’s critical that as an investor you conduct your own due diligence on the deal to access the viability of the returns promised by the syndication group. While there is a myriad of ways to structure a deal with a preferred return, this is how a basic pref structure works.

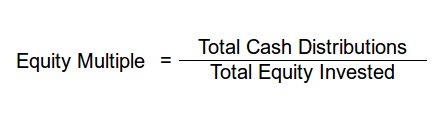

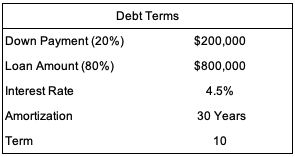

Equity multiple is a return metric used in commercial real estate which measures the total cash distributions received from an investment divided by the total equity invested. For example, if the total amount invested into an apartment property totals $500,000, and the total cash distributions including the sale of the asset equals $1 million, the equity multiple would be 2 ($1,000,000 / $500,000 = 2). If an investor’s equity multiple is below one then they will lose money, when it is equal to one they will break even, and anything above one means they will make money on their investment. Equity multiple is a relatively simple return metric compared to others such as IRR, cash-on-cash, or preferred return. While this return metric is simple to understand, it does not factor in the time value of money like the internal rate of return (IRR) formula. The nice thing about the equity multiple is that it can be converted to an annual return figure. In order to turn an equity multiple into an annual return figure an investor would use the following formula (equity multiple – 1 / years). Using the above example of the 2 equity multiple and dividing it by a 5-year time period would yield an annual return of 20% (2 -1 / 5 =20%). More so, the equity multiple can be used to value two separate real estate deals once an investor converts the equity multiple of both deals to annual figures. For example, let’s say that an investor has two separate real estate deals and deal one has an equity multiple of 2 with a five year hold period while the other has an equity multiple of 2.5 with a ten year hold period. The illustration below shows the annual returns an investor could expect to receive from both investments.

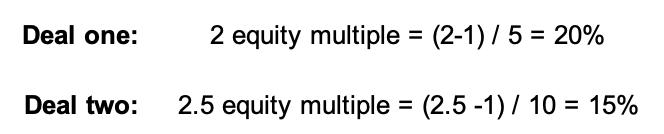

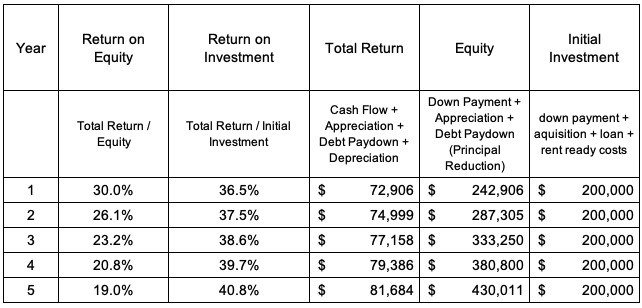

Return on equity (ROE) is a profitability metric used in real estate to measure how much profit is made on an investment property as a percentage of the equity in the property. In order to calculate this metric, you take the yearly cash flow, appreciation of the property, debt paydown, and depreciation and divide it by the equity in the property. Return on investment on the other hand is similar to ROE in the sense that it is a profitability metric, however instead of measuring the profit based on how much equity you have in the deal, it measures profit based on the initial investment. With this knowledge, let’s go over an example. Let’s say an investor buys a $1 million property and puts 20% down (this would be $200,000 and is the initial investment). The investor finances 80% of the property ($800,000) at a 4.5% interest rate with thirty years of amortization for a ten-year term. Yearly the property generates $30,000 in net profit (increasing 2% yearly) and it appreciates by 3% annually. Below I have provided a graphic of the return on equity and return on investment that the investor could expect to receive over the course of five years. Notice how much the ROE and ROI vary from one another. Since the return on investment metric is based only on the initial investment, the denominator of the equation does not change and thus does not take into account principal paydown amongst other factors. Return on equity on the other hand accounts for adjustments in how much equity you have in the deal and as a result is a better way of calculating return over the span of an investment. Something we must remember is that properties don’t always appreciate in value and can also stagnate in value or dare I say depreciate. Also, investors aren’t always able to increase rents as they may have thought at the onset of a real estate investment. Nevertheless, given that you’ve done your homework on the market you choose to invest in, you should see sizable appreciation in your property over the long term.

A straight split is one of the most simple multifamily structures to understand. A straight split is when the net cash flow and profits are split between the limited partners (passive investors) and the general partners (the deal sponsor). In a straight split scenario, the limited partners are favored. Here are some common straight splits in multifamily syndications:

- 90% LP / 10% GP

- 80% LP / 20% GP

- 70% LP / 30% GP

- 60% LP / 40% GP

Syndicators usually structure their deals with a 70/30 split or an 80/20 split when choosing this type of structure. The good part about this type of structure is that it is a win-win for passive investors and the syndicators. When the property performs well, everyone will profit. Below I have outlined an example in which a deal was acquired and the total equity raised was $498,682. The split that I assumed was 70% to the LPs and 30% to the GPs. You can see that after debt payments there was $37,135 (“Cash Flow available for Distribution”) in profit that was able to be distributed. After calculating the split, the limited partners (referred to as “Members” in the table) received $25,995 while the GPs received $11,141. As a side note, you can see that the cash-on-cash return (total cash flow distributed / total equity in the deal) is 5.21% ($25,995 / $498,682).

This structure is favorable for a “set it and forget it” type scenario in which the business plan involves holding the deal and simply distributing cash flow on a regular basis. The drawback of this type of structure is that if the deal performs poorly (i.e. little to no cash flow available for distribution) then the investors and the GP don’t get much or any return from the deal.

Many syndications today are structured with a preferred return, also known as a “pref.” A preferred return is a percentage return given to passive investors before the sponsor can receive even a penny. Before going further I want to point out that the sponsor’s share of the profit after the return hurdle has been paid is sometimes referred to as the “promote.” In today’s market, preferred returns range anywhere from 6%-9% in multifamily offerings. Preferred returns are calculated by multiplying the preferred return of a given deal by the total equity put into the deal. An important distinction to note is that preferred returns can refer to an internal rate of return hurdle or a simple percentage of the capital account.

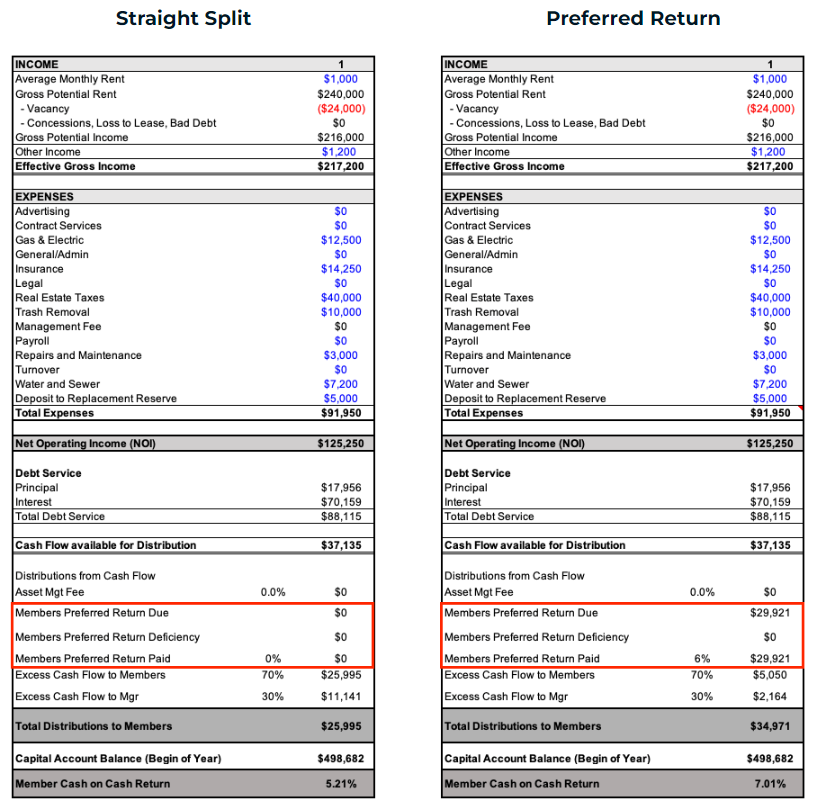

I’ve put a side-by-side scenario of a deal in the images below. On the left, you can see a straight split structure. On the right is the preferred return structure. In the straight split structure after calculating the split, the limited partners (referred to as “Members” in the table) received $25,995 while the GPs received $11,141. In the preferred return scenario, the limited partners received a total of $34,921 ($29,291 + $5,050). The return is higher for the limited partners in the pref scenario because they received a 6% return which amounted to $29,921 and the remaining 70/30 split summed up to $5,050. The 6% return was calculated by multiplying 6% by the capital account balance (i.e. the equity put into the deal) and in mathematical terms, it looks like this: 6% * $498,692 = $29,921. You’ll notice that the general partners received a smaller share of the profits in the preferred return scenario because the 6% return had to first be distributed to the limited partners before the general partner could participate in the profit sharing. A nuance that I’ll note is that the pref structure below assumes that the general partners had not put any capital in the deal. Had the general partners put equity in the deal, their equity contribution would be treated the same as the limited partners.

A great aspect of preferred returns is that they accrue. This means that if the sponsor team doesn’t meet the preferred return in one year, they must supplement the next year’s return with what was not paid in the previous year. In the image below, I took the same deal we’ve been working with but artificially boosted the expenses by adding a 10% management fee (calculated by taking 10% of the “effective gross income”). You can see that since the preferred return was not able to be met in year 1 and only $15,415 was paid of the total $29,921 pref, the preferred return accrued to the amount of $14,505 (referred to as “Members preferred Return Deficiency” in the image). The $14,505 shortfall was calculated by the ability of the sponsor team to only be able to pay off $15,415 (the cash flow) of the total $29,921 pref. As a result, in year two the $40,266 available for distribution covered a majority of the shortfall however there still wasn’t enough cash flow to cover all of the pref which resulted in $4,160 to be owed to the limited partners in the following year. If I extended this scenario to year 3 you would have seen the $4,160 be paid off in addition to the pref that was owed and then followed by the remaining cash flow being split 70% to the limited partners and the remaining 30% to the general partners. I’ll note that not all syndications are structured in a way that the pref accrues. Some sponsors incorporate a pref in the deal structure, but it doesn’t accrue, negating the investors’ downside protection. More so, in a pref structure, the general partner is incentivized to make the deal run in the most efficient way possible so they can earn a portion of the profit. In a straight split structure, the sponsor knows they will get paid regardless of how the deal performs so long as there is money available for distribution. The pref structure allows for trust and accountability to be built with the deals sponsorship team (the general partner).

Waterfall structures can get increasingly complicated with each additional hurdle. A “waterfall” can be thought of as a series of pools in which cash flows to one entity or individual to fill a single pool before spilling over to the next one. In other words, a waterfall is used to describe how limited partners and general partners are repaid through a share of distributions. The preferred return structure is one example of a waterfall structure because the pref ‘pool’ so to speak must be filled prior to any straight split taking place. The waterfall structure is usually based on a type of return hurdle that must be met in order to progress to the next level of the waterfall. There are a variety of waterfalls that can take place and this type of structure is most commonly used when a sponsorship team partners with a sophisticated private equity firm. As more and more layers are added to a waterfall, the structure becomes more complex. An example of a complex multilayered waterfall based on multiple return hurdles is shown below.

- 6% preferred return

- 80/20 split of profits until passive investors (limited partners) receive a 10% internal rate of return (IRR)

- Then, a 70/30 split until investors have reached a 12% IRR

- 50/50 split between limited partners and sponsors

What the IRR return hurdle does is ensure that the limited partners get their initial investment back. Something important to note is that the IRR calculation isn’t positive unless the initial capital of the investors is returned. As a result, this complex waterfall structure incentivizes the sale of the asset or a refinance in which 100% of the capital is returned to investors so that the IRR can become positive. This is true because it takes a lot of capital in order to return the total equity that the investors put into the deal. Cash flow alone almost always will not get you to a positive IRR relatively quickly (less than 5 years) unless the cash flow from the property is incredibly strong (this is unlikely). Furthermore, this structure provides the strongest incentive for the general partners to perform well because of the IRR hurdle. In addition, this structure incentivizes the general partner to put up more capital so that the IRR hurdle can be met quicker. It is likely that as a limited partner you will see the preferred return structure explained in the previous section more often than this complicated waterfall structure. However, it is common as deals get larger that the sponsor incorporates a complex waterfall structure will IRR hurdles, and in those deals because of a large amount of capital required, usually, a sophisticated private equity firm comes into the deal.

Let’s keep things a bit more simple and say that there is an IRR hurdle of 10% with a 50/50 split thereafter. This means that once the investor achieves a 10% IRR on capital invested in the deal in the form of cash distributions, refinance proceeds, and sale proceeds from the project, anything after is a 50/50 split. This would be an example of where investors achieve a solid target of 10% IRR, and the project’s general partners (the sponsorship team) receive a bonus for hitting those return hurdles (i.e. the promote). A nuance to this is that sometimes the preferred return is compounding. What this means is that any shortfall in distributions in one year is then multiplied by the pref percentage and owed in the next year. The compounding preferred return can be complicated to understand and I won’t dive into it but is nonetheless an important aspect to note.

For those of you that want to dive deeper into the weeds, I want to make you aware of a complicated private equity (PE) structure that could take place. This “complicated” PE structure involves a catch-up provision which means that the limited partners receive 100% of distributions until they achieve some preferred return requirement (whether an IRR hurdle or simple pref calculated as a percentage of equity committed to a deal). With a catch-up provision, once the limited partner receives their pref, the general partner receives 100% of excess cash flow until some equitable balance is reached (that balance is usually a percentage of all cash flows received up until that point). For example, imagine a limited partner contributes 100% of the required capital to a real estate deal for a 12% preferred return and 50% of all excess cash flows above that threshold. The catch-up provision states that the limited partner will receive 100% of all cash distributions until they have earned a 12% IRR, at which point the general partner receives 100% of cash distributions until both partners have received 50% of profit distributions. Once the general partners have caught up with the limited partners, both partners receive any remaining cash flow 50/50. This structure with a catch-up provision is unlikely to be seen unless there is a private equity firm investing in the deal at hand.

Legal

To establish an LLC, an investor must file a document titled “Articles of Organization” with the state agency responsible for business filings. This document is rather simple and typically contains the business name and address as well as the address of the individual who can receive lawsuits on the business’s behalf. Depending on the state, the articles could include the names of the owner(s) (members) or managers of the LLC in addition to the purpose of forming the entity. The filing fees typically run about $50 for legal services and $50 to upwards of $800 for a filing fee which of course depends on the state. To make things easier to remember, the full list of information that you’ll need to include in your Articles of Organization includes the following:

1. Business Name

2. Address of the LLC

3. Business Mailing Address

4. Business Purpose

5. Members’ and/or Managers’ names

6. The state law (this is usually pre-printed on the form)

7. Effective Date

8. Registered Agent’s details – this is the person who receives legal documents on behalf of your company

9. Duration of the LLC – can be perpetual of indefinite

A letter of intent (LOI) is a non-binding document that outlines the terms by which two or more parties intend to later formalize a binding agreement. In simpler terms, an LOI is what a buyer submits to a seller of a multifamily property which outlines under what terms the buyer wants to purchase their property. The LOI avoids wasting the time of all the parties involved because if the LOI isn’t accepted, the process of hiring a lawyer, conducting due diligence, and more is avoided. The terms of the LOI include the purchase price, down payment and loan terms (if you’re using financing), earnest money, conditions/contingencies, broker commission, how long the buyer has to perform due diligence, and more. Usually, the buyer and seller will go back and forth with the LOI and either reach a point to where both parties are in agreement of the terms or perhaps not reach an agreement. Once the letter of intent is signed, the due diligence period starts for the buyer and they will receive access to the property (as stated in the LOI) to perform due diligence. As the due diligence is being done, the seller’s lawyer will draft the purchase and sale agreement (PSA).

An operating agreement is an internal document that describes how the investor’s LLC will run in addition to the roles and contributions of the owners (members) and the way decisions will be made. An investor can create their own operating agreement for free. However, if there are multiple members to the LLC then the investor will want to make sure to get professionals involved to make sure the process goes smoothly and the information is accurate. This document can be done by a legal service provider which typically will charge between $50 and $200 or you can hire a local lawyer to get this done. The details of the operating agreement will include the following:

1. General Character of Business – The purpose of the LLC

2. Separateness – (ex. I’ve seen: “The Company must conduct its business and operations in its own name and must maintain books and records and bank accounts separate from those of any other person.”)

3. Management – The person or entity that will manager the entity (i.e. the LLC)

4. Allocation of profit and loss – How the profits and losses will be split (ex: All distributions with respect to the Managing Member’s interest in the Company will be made 100.00% to the Managing Member)

5. Capital Contribution – Initial capital contribution going to the company

6. Dissolution– When the company will seize to exist

7. Fiscal Year– The year for taxing and accounting purposes (usually the calendar year)

8. Taxation as Partnership– (ex: The Company shall file its return with the Commissioner of Internal Revenue and any applicable state taxing authorities as a partnership and shall not elect to be taxable other than as a partnership without the consent of the Member)

9. Tax Matters Partner / Partnership Representative – This is the member of the partnership who is responsible for representing the business to the IRS in the fiscal year stated on the form. (ex: The Member is hereby designated the Tax Matters Partner for the purposes of Section 6231(a)(7)(B) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended from time to time. The Tax Matters Partner shall comply with the responsibilities set forth in Sections 6221 through 6234 of the Code.)

10. No Liability of Member and Others – A statement spelling out that the members of an LLC are not personally liable for the debts of the company unless the Articles of Organization states otherwise or the members agree to be personally liable.

11. Indemnification – This is a statement saying that the LLC will hold harmless ant member, manager, or other person from any and all claims or demands whatsoever.

12. Amendment- Here in the operating agreement it states the Articles of Organization may be amended only by written agreement executed by the members.

13. Governing Law- This part of the OA states that the document will be interpreted and enforced in accordance with the state that it was filed with.

The purchase and sale agreement is the document that is written up and signed after a buyer and sale mutually agree on the price and terms of a real estate transaction. This can be thought of as the legally binding version of the letter of intent and once this document is signed, it cannot be broken. The PSA sets forth terms such as the purchase price, financing, closing terms, inspections and surveys, property conditions, and other constraints/contingencies that both parties must abide to. The PSA can take several weeks to finalize and while this document is very long, it’s essential that both parties read the contract to make sure they understand all aspects of the transaction.

The private placement memorandum is a document drafted by one’s attorney which provides investors with all the information they need about a real estate syndication or fund to make an informed decision as to whether they want to invest or not. The document contains important information such as the operating agreement, investor questionnaires, subscription agreements, risk factors associated with the deal, business plan, projections, sources and uses of the funds, etc. A PPM is used in private transactions when the security (in real estate, the security would be the property) is not required to be registered with the SEC. In other words, the PPM is similar to the prospectus public companies provide when issuing a public offering, however, a PPM is for private transactions.

There are many ways to invest in real estate and at JP Acquisitions we syndicate deals under Rule 506(b). A syndication is a partnership between multiple individuals that pools resources, capital, and talent to enable the acquisition/purchase of an apartment building. Syndications allow investors to acquire larger properties which might have been difficult if someone were to do it themselves. Syndications are composed of general partners (GPs) and limited partners (LPs). General partners manage the deal while limited partners are the investors. LPs invest in syndications for ownership, returns, and tax benefits and rely upon the general partners to deliver upon the business plan of the syndication. A syndication can be done on various types of real estate such as apartments, mobile home parks, self-storage, senior housing, student housing, developments, etc. While the asset can vary, the principal is the same and that is to invest in a real estate asset through the combined capital of GPs and LPs to deliver a return. With that being said, let’s dive a bit more into what makes a real estate syndication possible.

In 2012, the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Acts (JOBS act) was signed into law. At that point in time the existing Regulation D Rule 506 was split into two sections: 506b and 506c. Rule 506 is a Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulation that allows businesses to raise private capital with securities (such as equity shares) that are exempt from SEC registration. Rule 506 is beloved by real estate syndicators because it allows them to raise an unlimited amount of money, sell securities to an unlimited number of accredited investors, not have to register the security (in this case real estate) with the SEC, and not have to meet any state-specific filing or other requirements. The original rule prior to the JOBS Act, known as Rule 506(b), allows businesses to raise as much capital as they would like from an unlimited number of accredited investors, and up to 35 sophisticated investors. An accredited investor and a sophisticated investor can are defined as the following according to the SEC:

Accredited Investor: Anyone who earned at least $200,000 for the past two years and is expected to have an income of $200,000 in the current year. Investors who do not meet the income requirement but have a net worth of $1 million (excluding their primary residence) are considered accredited investors. For couples to qualify, their income must be at least $300,000 or they meet the same net worth requirement.

Sophisticated Investor: These investors do not meet the income or net worth requirements to be an accredited investor, but have adequate experience and/or knowledge in business, finance, and investments in order to evaluate the risk/reward of an investment.

Under the rules of 506(b), investors can go through a self-certification process that confirms they meet the definition of a sophisticated or accredited investor. What’s important to note is that under rule 506(b), companies or sponsors are not allowed to use any form of marketing to promote their deal offering. In order to comply with this law, the sponsor must prove a subsequent and pre-existing relationship with the investor before they present an investment offering.

The new rule after the JOBS Act, 506(c), allows issuers who are selling securities to generally advertise as long as they make the offerings to accredited investors. If someone is not an accredited investor, they are not eligible to invest in 506(c) syndications. Self-certification is not allowed under rule 506(c) and an issuer must follow steps to verify their investors are accredited at the time they make their investment. From the investor’s standpoint, they must have the issuer review or hire someone to review the investor’s financial information (W-2s, tax returns, brokerage statements, and credit reports).

Key principals (KPs) are guarantors that provide either past experience, net worth, or liquidity to a deal. Whether a lender is offering a resource or non-recourse loan, they want to see someone on the sponsor’s team who helps mitigate the risk for the lender. In essence, KPs are involved in deals because they make up for the lack of either past experience, net worth, or liquidity which the sponsor(s) does not have. KPs can have a passive role in a deal or a more active one depending on what is agreed upon between the sponsor and the KP. Oftentimes KPs are compensated for what they bring to the table by getting a portion of the general partners/sponsor’s fees. Something that I should note is that the general rule of thumb when taking out a loan is that the sponsor group needs to have a combined net worth equal to 100% or more of the loan amount and 10% or more post-liquidity. Also, lenders will do background checks in addition to checking the personal financial statements (PFS) of the sponsor team and KP(s) who are backing the loan. One final thing I should note is that KPs are not necessary if the sponsor group meets the experience, net worth, and liquidity requirements the lender is looking for.

A deed is a written legal document that transfers ownership of a property from one party to another. It serves as evidence of the transfer of ownership rights. When a property is sold or transferred, the seller or grantor prepares a deed, which is then signed and delivered to the buyer or grantee. The deed typically includes information such as the names of the parties involved, a legal description of the property, and any relevant conditions or restrictions. Deeds need to be signed, notarized, and recorded with the appropriate government office, usually the county recorder’s office, to be legally valid. There are different types of deeds, such as warranty deeds, quitclaim deeds, and special warranty deeds, each providing different levels of protection to the buyer.

There are some exceptions to the rule that a deed is required to transfer a property (hence why it states “usually” in the table below). One example is if a property is inherited, the title may be transferred without a deed. However, in most cases, a deed is the best way to ensure that the transfer of ownership is legally valid.

The title refers to the legal right to ownership and possession of a property. It represents a bundle of rights associated with the property, including the right to use, occupy, transfer, or sell it. A title is not a physical document but rather a concept of ownership. When a property is purchased, a title search is conducted by a title company or an attorney to ensure that the title is clear and free from any liens, encumbrances, or other claims. The title search examines public records to verify the ownership history and determine if there are any issues that could affect the buyer’s rights to the property. Once the title is deemed clear, the title company or attorney may issue a title insurance policy, which protects the buyer against any future claims or defects in the title.

In some jurisdictions, a title may be required to transfer a property even if there are no title defects (hence why it states “sometimes” in the table below). This is because the title is a legal document that is recognized by the government.

Debt

Debt refers to money that is lent with the obligation of the borrower to repay the full amount plus interest on a regular basis (usually monthly). Before providing a real-life example of a loan taken out on a multifamily property, let’s run through some of the the terms you’ll need to know

Loan amount: This refers to the amount that is owed to the lender. For example, an investor may take out a loan for $250,000. That $250,000 is referred to as the loan amount.

Payment term: This is the description of the proposed payment structure. For a standard loan, payments are typically due monthly.

Maturity: This refers to the date on which the borrower’s final loan payment is due. A loan may reach maturity in whatever period of time an investor has settled upon with the lender.

Principal: When making payments on a loan, part of the loan is used to pay off the actual loan (principal), meanwhile the remainder of the payment is used to pay off interest. The portion of a payment that goes to paying off the loan is referred to as a principal payment.

Interest: Interest is essentially the charge for the privilege of borrowing money. Interest rates vary depending on what the Federal Reserve sets the federal funds rate at. For example, the current average interest rate for a 30-year fixed mortgage is 7.32%.

Amortization: This refers to the period in which a loan is reduced or paid off by regular payments.

Collateral: This is something pledged as security for repayment of a loan in the event that the loan can not be paid off.

Guarantor: When a bank is lending out money they want personal guarantees of the individuals involved in the transaction. A guarantor is a financial term describing an individual who promises to pay a borrower’s debt in the event of a default. Loans can also be non-recourse which means that no personal guarantees are required by a lender.

Recourse/Non-Recouse: A recourse debt holds the borrower personally liable in the event of default. On the other hand, non-recourse debt does not hold the borrower personally liable.

Now that you have a general understanding of debt terms, let’s use an example to get a better understanding of what it means to take out a loan on a property. The following is a real life example of a loan that was taken out on a 8-unit $800,000 property. The investors negotiated with the bank to take on a loan for the $800,000 property in which they required a down payment of 23.75% ($190,000) with 25 years amortization at a 4.3% interest rate for a 10-year term (maturity) with payments to be made monthly. Since the investors did not meet the liquidity requirements to take on the loan, the investors found an outside guarantor to carry the loan and pledge his assets as collateral in return for a percentage of the profits. As a result of the terms, the loan was structured in a way that it would become due in 10 years (the term) while the payments were sized as if the loan would be paid off in 25 years (this refers to the amortization). Given those terms, the year one principal payment was $13,784, while the interest payment amount was $25,737 for a total payment of $39,521.

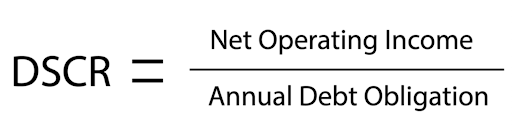

Debt service coverage ratio (DSCR), also known as debt coverage ratio (DCR), is a metric that looks at a property’s income compared to its debt obligations. This metric is calculated by dividing the annual net operating income (NOI) of a property by the annual debt obligation. For example, if a property has an NOI of $65,000 and the debt service is $40,000, then the DSCR is 1.625 ($65,000 / $40,000). Properties with a DSCR above one are considered to be profitable, while those with a DSCR of less than one are losing money. DSCR is an essential part of the decision-making process when a commercial or multifamily lender decides to issue a loan. In general, the majority of lenders like to see borrowers have a DSCR of at least 1.25x. The reason why lenders like to see this DSCR is that they can feel confident knowing that if a property experiences a lower NOI for whatever reason (higher vacancy, expenses, etc.), the debt can still be paid. The higher DSCR that a property is forecasted to have, the more likely a borrower is to get preferential debt terms. For example, if a property has a DSCR of 1.10, that property has a low margin of safety. The chance that higher expenses or vacancies cause them to not be able to make debt payments is too high for most lenders to feel safe. To mitigate the risk, the lender may want the borrower to put down more money so as to decrease the debt payments and strengthen the DSCR as a result. Remember, the larger the down payment an investor makes on a deal, the smaller the debt payments are.

As a side note, I introduced the term margin of safety in the last example and that term refers to the chances of losing money in an investment. The higher the margin of safety, the less likely chance there is to lose money in an investment. It’s important to understand that when vetting an MF deal that the property being analyzed needs to have an adequate DSCR (preferably above 1.35) so as to be confident that if things go south the debt can be paid and the bank won’t foreclose the property.

A bridge loan is a short-term financing tool used until an investor can secure permanent financing. These types of loans come with interest-only payments which means that the borrower has to cover only monthly interest charges for the entire loan. Once the term of the loan is finished, a balloon payment must be made to pay down the balance. A balloon payment refers to the total lump sum of a loan paid at the end of a loan’s term which is significantly larger than all other payments made until then. Bridge loans can last anywhere between three months to three years and have higher interest rates than fixed-rate loans. These loans are typically used to finance the construction or rehabilitation of a property. For example, let’s say an investor purchases a $1 million property that is severely distressed and needs major rehab work done. The property is not generating income and thus the investor cannot get a traditional fixed-rate loan and therefore opts in for a bridge loan. The total cost of the renovations will be $300,000 and the bank says they’re willing to finance 80% LTC (loan to cost) at 6.5% interest for twelve months. The bank in total will provide $1.04 million (($300,000 + $1,000,000) * 80%)) and the rest is to be financed by the investor. Once the renovations are complete, the investor will lease up the building until it is stabilized (90%+ occupancy) so that the building appraises at a value large enough so that when they take out a traditional fixed rate loan it is large enough to cover the balloon payment of the bridge loan. This is a simplified example of how an investor may use a bridge loan to finance the rehab plan of a property. I should note that some lenders will finance the cost of the property in addition to the rehab/construction budget (this is referred to as loan-to-cost), while others will only be willing to finance the value of the property (loan-to-value). Whether a lender chooses LTC (loan-to-cost) or LTV (loan-to-value) when providing financing options depends on the risk of the business plan. Nevertheless, because there is more risk with bridge loans, the interest rates lenders charge on this type of loan are higher than that of fixed-rate loans. The good news is that while the interest rate may be high, bridge loans tend to close fast and have extension options if needed.

A step-down prepayment penalty is a predetermined sliding scale in which the amount of the penalty is based upon the principal balance of the loan in addition to how much time has passed. The most common scale for this prepayment penalty is 5%, 4%, 3%, 2%, 1%. For example, if an investor pays off a loan in the first year, they will have to pay a fee equal to 5% of the outstanding loan balance. If the investor pays off the loan in the second year, then they will have to pay 4% of the outstanding loan balance. This declining scale keeps repeating until the prepayment penalty no longer applies. Using the example from before, if the investor pays off the loan in year six, then they will not be hit with a prepayment penalty.

The pros of this prepayment structure are that it’s straightforward and easy to predict. In addition, it’s a good option in a declining or flat interest rate environment relative to yield maintenance and defeasance. A con is that some 10-year fixed-rate loans have prepayment penalties that start at 10% and decrease by 1% every consecutive year. That would make it difficult to pay off the loan in the early years and an investor might be better off with one of the other prepayment penalties. Another con is that this structure can be a poor choice in an environment where interest rates are rising.

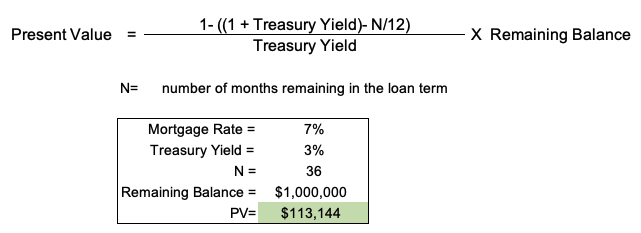

Yield maintenance is more difficult to understand then step-down, but in essence it’s designed to maintain the lender’s yield (aka their return on investment) throughout the fixed rate period of a loan. Before diving into the math, here’s how it works: in the event that rates have stayed flat or declined since an investor closes a loan, the lender profits on the present value of the difference between the interest rate on the loan and the current yield on the US treasury bond which most closely matches how many years the investor has left on their loan. Stated differently, if an investor gives back the lender their money prematurely, the investor will need to compensate the lender for the money they will lose having to invest in the lower return/yielding government bonds. If rates have risen to the point that yields the prepayment penalty negative/negligible, usually a 1% minimum will be charged to the investor.

The pros of this prepayment penalty are that if rates rise enough then an investor may only have to pay a 1% penalty which is reasonable. In addition, in a rising rate environment, an investor’s property may be worth more if the loan on the property is assumable. In other words, if interest rates are higher than that of the assumable loan, then an investor who assumes the loan will pay more for a property knowing their interest payments on the assumable loan will be less than that of market rate loans. A con is that if interest rates remain the same or decrease, an investor could be left with a high prepayment penalty.

Consider this example, an investor wants to pay off their outstanding loan balance with three years (36 months) remaining in the repayment term. The investor was originally issued a 10-year loan at a 7% interest rate of which $1,000,000 is remaining. The investor goes on the U.S. Department of Treasury website and sees that the three-year treasury yield is 3% (notice how this investor has three years remaining on his loan and they take into account the three-year treasury in the calculation). The present value formula and math are shown in the illustration below. While I won’t explain all the mechanics behind this equation, we provide a yield maintenance calculator available for download on our website under the “education” tab.

Defeasance is the most difficult prepayment penalty to understand and requires several professionals including attorneys, a loan servicer, a third-party defeasance processor, and a bond rating agency or CPA’s to execute the process. In simple terms, a defeasance is the process of an investor taking the sale proceeds of a property to buy a security (usually a treasury bill) that matches the payment schedule of the loan that was paid off. The security would take the place of the payments that would have been made if the loan was never paid off in the first place. In a way, defeasance is similar to yield maintenance because the lender preserves their yield/return.

The cons to defeasance are that is it difficult to understand/calculate and also requires a cast of professionals in order to finish a transaction which adds additional costs. The pro is that in theory, it’s possible to pay off one’s loan at a discount if rates rise fast enough.

Taxes

Form 1040 is the standard form for individual income tax returns.

- Real estate investors, including those in multifamily syndications, report their personal income, deductions, and credits on this form.

- Income from real estate activities, such as rental income, may flow through to this form from other forms like Schedule C, E, or K-1.