Terminology Multifamily Investors Should Know (Part 1)

November 6, 2022Terminology Multifamily Investors Should Know (Part 3)

November 21, 2022This is part two of a multi-part blog series on multifamily real estate terminology (part one can be found here). The terms found in this post, in addition to the previous one, apply to real estate in general and not only to multifamily real estate. The goal of this series is to provide investors with an understanding of the necessary terminology to speak on and underwrite multifamily deals confidently. With that being said, in this post I will touch on the following terms: equity, debt, appreciation, internal rate of return (IRR), and building classifications. I shall note that the terms in this blog series are not laid out in a specific way and therefore I leave it up to you to use the knowledge you gain from these posts to create a coherent picture of the multifamily landscape.

Equity

Equity in real estate refers to the value of a building less any debts owed on the property. For example, let’s say that the fair market value of a building is $1,000,000 and I purchase the property for $900,000 from a motivated seller. I finance the property with a 10-year mortgage with 30-year amortization at a 5% interest rate and put down 20%. For now, focus on the down payment and not the other terms I mentioned for simplicity’s sake. The property has an annual appreciation rate of 3% in this scenario and equity is created in a number of ways. Firstly, $100,000 in immediate equity is created ($1,000,000 – $900,000 = $100,000) since I bought the property at below fair market value. The down payment of $180,000 ($900,000 * 20%) also becomes immediate equity. Over 5 years the value of the property increases by $259,274 (($1,000,000*(1.03^5)-$900,000)) which becomes equity. Finally, the number of mortgage payments applied toward the principal also incrementally increases the equity each month until the property is sold.

Investors who purchase wisely and use leverage conservatively and appropriately can more often than not grow equity throughout their holding period. The longer the holding period, the more equity built up in a property. This is true not only through the principal payments made on a mortgage, but through market appreciation (more on this to come in the appreciation section). In addition, an investor could increase their equity on a property through renovations. Going back to the example, if I had chosen to renovate the property through various upgrades (adding new appliances, flooring, etc.) then the fair market value of my property would be higher. I should note that sometimes equity can be negative and that occurs when the value of a property is less than that of the debt owed on a property. For example, if I have an outstanding mortgage on a property that is $1,000,000 and the fair market value of the property is only $950,000, then I would have negative equity of $50,000. Nevertheless, for as long as an investor buys a property in a strong market (characterized by job growth, low crime, increasing household incomes, population growth, etc.), then the odds are that the investor will increase equity in their property and come out with a gain when the building is sold.

Debt

Debt refers to money that is lent with the obligation of the borrower to repay the full amount plus interest on a regular basis (usually monthly). Before providing a real-life example of a loan taken out on a multifamily property, let’s run through some of the the terms you’ll need to know

Loan amount: This refers to the amount that is owed to the lender. For example, an investor may take out a loan for $250,000. That $250,000 is referred to as the loan amount.

Payment term: This is the description of the proposed payment structure. For a standard loan, payments are typically due monthly.

Maturity: This refers to the date on which the borrower’s final loan payment is due. A loan may reach maturity in whatever period of time an investor has settled upon with the lender.

Principal: When making payments on a loan, part of the loan is used to pay off the actual loan (principal), meanwhile the remainder of the payment is used to pay off interest. The portion of a payment that goes to paying off the loan is referred to as a principal payment.

Interest: Interest is essentially the charge for the privilege of borrowing money. Interest rates vary depending on what the Federal Reserve sets the federal funds rate at. For example, the current average interest rate for a 30-year fixed mortgage is 7.32%.

Amortization: This refers to the period in which a loan is reduced or paid off by regular payments.

Collateral: This is something pledged as security for repayment of a loan in the event that the loan can not be paid off.

Guarantor: When a bank is lending out money they want personal guarantees of the individuals involved in the transaction. A guarantor is a financial term describing an individual who promises to pay a borrower’s debt in the event of a default. Loans can also be non-recourse which means that no personal guarantees are required by a lender.

Now that you have a general understanding of debt terms, let’s use an example to get a better understanding of what it means to take out a loan on a property. The following is a real life example of a loan that was taken out on a 8-unit $800,000 property. The investors negotiated with the bank to take on a loan for the $800,000 property in which they required a down payment of 23.75% ($190,000) with 25 years amortization at a 4.3% interest rate for a 10-year term (maturity) with payments to be made monthly. Since the investors did not meet the liquidity requirements to take on the loan, the investors found an outside guarantor to carry the loan and pledge his assets as collateral in return for a percentage of the profits. As a result of the terms, the loan was structured in a way that it would become due in 10 years (the term) while the payments were sized as if the loan would be payed off in 25 years (this refers to the amortization). Given those terms, the year one principal payment was $13,784, while the interest payment amount was $25,737 for a total payment of $39,521. While I won’t run through the payment calculation, I’ve provided a link to a multifamily loan calculator as well as a link to how to calculate the payments yourself.

Links:

How to calculate debt payments

Appreciation

In real estate, the term appreciation refers to the increase in the value of a property over time. There are two ways in which your property can increase in value, through forced appreciation or through macro factors. Forced appreciation occurs when a real estate investor actively seeks to increase the value of a property by increasing rents, identifying additional ways to generate income, reducing expenses, or a combination of the three. Rents can be increased by simply bringing them up to market (assuming they were not there before) or by implementing renovations so as to make the units more attractive, which in turn will make them more desirable so as to command a higher rent. From a macro level, appreciation may result from inflation, increased job opportunities in the market, overall development in the area, or a combination of the three. I should note that appreciation can be a result of inflation because historically rents have increased at the same rate as inflation. Market factors can increase property values as well because as an area becomes more desirable due to a number of factors (increased jobs, population growth, developments in the area), landlords will increase rents. What’s important to remember is that higher rents increase the value of a property because increasing rents translates to higher income. The more income a property makes, the higher valuation that it commands.

Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

Internal rate of return (IRR) is the most popular method used for identifying the return from a real estate investment. When considering an investment in a multifamily property the question that you must ask yourself is, “If I invest in this property, what is the return I can expect?” IRR is designed to measure the compounded annual rate of return an investor can expect on their investment. IRR can also be thought of as the rate earned on each dollar invested for the time period it is invested in. The part of the definition that is important to focus on is “the time period it is invested in.” The time component of the IRR calculation cannot be ignored because it accounts for the compounding of returns. Mathematically speaking, IRR is the rate of return that sets the net present value of all future cash flows (positive or negative) equal to zero. To reiterate in more simple terms, IRR is a metric that tells investors the average return they have realized or can expect to realize from a real estate investment over time (expressed as a percentage).

The beauty of the IRR calculation is that it accounts for profit and time in a single metric. While the concept of profit is relatively straightforward and can be defined as how much cash an investment generates, the time component in the IRR calculation is more nuanced. When I say “time component,” I’m referring to the time value of money. The idea behind the time value of money is that since inflation affects the value of money over time, a dollar today is worth more than a dollar in the future. For example, $1 today may only have $0.90 of buying power in 3 years due to inflation. In addition, since a dollar will be worth less in the future, each investment has a trade-off or otherwise known as opportunity cost. The idea of opportunity cost can be thought of as what an investor misses out on when choosing one alternative investment over another. What IRR allows investors to do is measure potential returns for various opportunities through one calculation all the while factoring in time. Thus, the IRR calculation provides the opportunity to value the potential returns for multiple investments which have different timelines. However, the calculation works best when looking at investments of the same time period.

Looking at the IRR calculation may give you flashbacks to the anxiety you had during high school calculus, but if you can understand this formula then you’re one step closer to being able to value potential real estate investments. The good news is that you can use the XIRR function in excel to do the hard work for you. Nevertheless, let’s look at a simple example to better illustrate the concept of IRR.

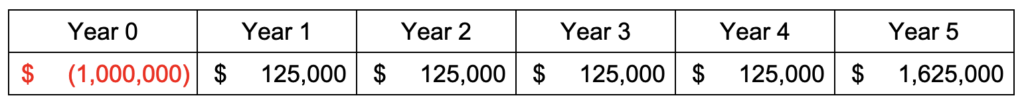

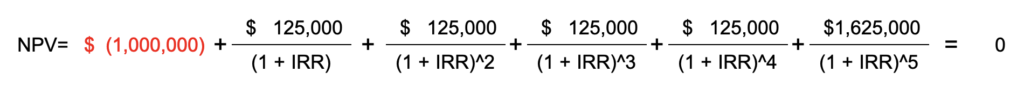

Let’s say that you buy a property for $1 million. Yearly you’ll earn $125,000 from rental income over four years. You plan to sell the property in five years for $1.5 million. Given these assumptions, set the net present value (link to definition) to zero to determine the IRR. You’ll notice that year 5 has increased cash flows due to the profit from sale in addition to the rental income. The result of the formula is an IRR of 19.31%. Below you’ll see the cash flow schedule in addition to the formula laid out to provide a visual representation.

While the IRR formula gives investors a prediction of what return they can expect on a property, IRR can be difficult to calculate without the right tools and because there is a lot of guesswork in terms of cash flows and sale price. Few investments go exactly as planned and therefore the IRR that an investor predicts at the onset of a project will more than likely change as time goes on. In addition, since IRR takes into consideration the time value of money, if you’re using yearly cash flow as opposed to monthly cash flow or vice versa for the calculation you will end up with two different numbers. I recommend calculating IRR based on monthly cash flows to get a more accurate picture of what your return will look like. Nevertheless, with this knowledge of the IRR calculation, you are better equipped to understand potential returns when considering various investment projects.

Multifamily Building Classifications

Multifamily investing can be broken down into four distinct building classes: class A, B, C, and D. It’s important that you have the ability to distinguish between the four building classes so as to enable you to determine which asset class best fits your investment objectives. With that being said, the lower you go down the class scale, the higher the cap rate gets and the reasons for why an investor chooses to buy the building changes.

Class A properties are the crème de la crème of multifamily assets. These properties are usually less than 10 years old and are luxury apartments. Class A properties are located in desirable geographic areas and the tenant base in these apartments typically consists of white-collar workers who usually rent by choice. Due to the location of these properties in addition to all of the amenities they offer (fitness center, business center, pool, rooftop lounge areas, etc.) the average rent is high. Class A properties generally have the highest valuation per door and the lowest market cap rates which means they’re usually purchased for appreciation.

Class B buildings are one step down from class A. These apartments can be 10 to 25 years old and are generally well-maintained. The tenant base includes both white and blue collar workers with some tenants renting by choice while the others by necessity. The cap rate for this building type is higher then that of class A. While class B apartments are primarily bought for appreciation, they generally have more cash flow than class A properties. The amenities in class B apartments are less impressive than that of class A buildings, however they normally offer some amenities that are enjoyable for the tenants.

Going further down the scale, C class apartments are typically built within the last 30 to 40 years and are comprised of blue collar and low-to-moderate income tenants. The tenants in class C apartments are usually renters “for life,” yet some of the tenants who are just starting out are likely to work their way up to nicer apartments as they progress in their careers. Rents for this asset type are lower than that of class A and B apartments due to the build, amenities offered, area, and other factors. These deals are attractive to cash flow investors and have higher cap rates than that of class A and B buildings. Many syndicators look for opportunities to turn class C apartments to class B apartments through renovations because they offer tremendous upside. At JP Acquisitions we look for class C properties which require the least amount of work to renovate in order to turn them into class B properties. We’ve found that this strategy of renovating class C buildings tends to yield the highest returns for investors, but opportunities to implement the strategy are far and few between in the markets we’ve studied due to demand.

Class D properties are the lowest on the class scale and are usually built more than 40 years ago. These properties typically house section 8 government subsidized tenants and are located in lower socioeconomic areas. While these properties have the highest cap rates of any property type, there are a number of factors to be aware of. Class D apartments tend to experience higher vacancies, substantial deferred maintenance, and are located in high crime areas. More so, they can require intense management and heavy security. Investors normally shy away from these properties due to the reasons listed. For seasoned investors who have a strong sense of the market in which they invest in, these deals are attractive due to the high cash flow.

Now that you understand the various multifamily classes, you’re better equipped to find deals based on your investment criteria. What you’ll notice is that sometimes the line blurs between what is classified as a class B property and class C. On the other hand, class A and D properties stand out due to the characteristics I listed for each.

Conclusion

After diving into this post, I hope your knowledge of multifamily real estate strengthened. If you haven’t read part one of this blog series, I encourage you to do so and a link to that post can be found here. While some of the terms covered here are more difficult to comprehend, with further research you can understand them better and I have no doubt you’ll be better off if you do so. At JP Acquisitions we take our investor’s education seriously and if you have any questions I hope that you reach out to me or someone on our team so we can better help you understand the world of multifamily real estate.

As always, I hope that you’ve enjoyed reading this post as much as I have writing it. If you’re looking to invest in multifamily real estate with our firm, don’t hesitate to reach out to our team so we can schedule a meeting to go over your investment goals.

Best of luck!