Terminology Multifamily Investors Should Know (Part 5)

December 5, 2022Building Generational Wealth Through Multifamily Real Estate

December 19, 2022This is the final post on multifamily terminology that investors should know. A glossary page on the JP Acquisitions website is in the works and will be up within the next couple of weeks. It’s been a pleasure covering all these terms and rest assured that more terms will be added to the glossary in the future. Something I want to note about this post is that the last three terms (step-down, yield maintenance, and defeasance) are all different forms of pre-payment penalties. A prepayment penalty is a fee that some lenders charge if you pay off all or part of your mortgage early. To add to the confusion, lenders refer to prepayment penalties in a number of ways including “prepayment fees”, “unwinding costs”, “early termination fees”, “breakage costs”, “interest guarantees”, “exit fees”, or “prepayment privileges”. Nevertheless, understanding the various names of what is usually referred to as “prepayment penalties” will serve you well when working with lenders. Having said that, let’s jump into this post.

Ratio Utility Billing System (RUBS)

In many older multifamily properties, units are not individually metered, making it hard for landlords to charge back tenants based on their usage. While individually metering each unit is an option, it may come with an unjustifiable price tag. A solution to that is to implement the ratio utility billing system (RUBS) which allows for a landlord to determine a tenant’s utility bill based on factors such as unit square feet, number of people living in the unit, number of bedrooms and bathrooms, and number of water fixtures. RUBS is essentially a way for landlords to reduce their utility expenses all the while increasing rent.

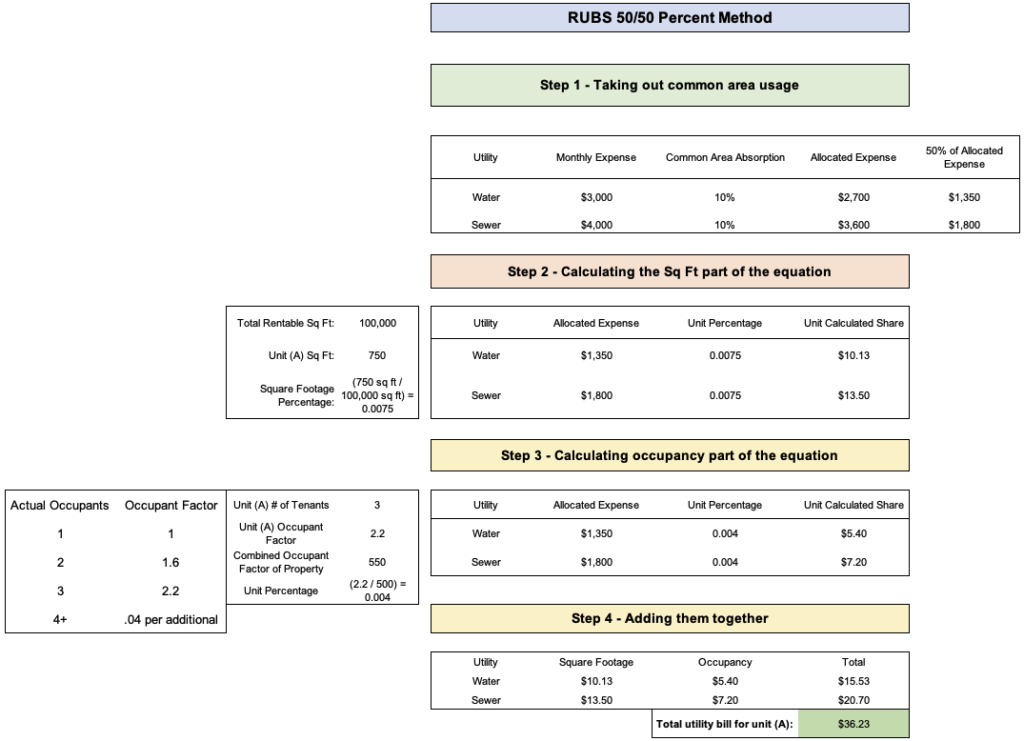

There are a number of ways to calculate RUBS and in this post I will show you the 50/50 split method. This way of calculating RUBS takes into consideration the occupancy as well as the square footage of a unit. Below I have provided a step-by-step illustration of the example I am going to outline for better comprehension.

Let’s say that an investor buys an apartment building and wants to calculate the amount of increase in rent that will cover the utility expenses for water and sewer for one unit type. The monthly expenses for water and sewer are $3,000 and $4,000 respectively. The investor takes out 10% of those expenses to account for the common area and then splits the remaining expenses by 50% (step 1). The investor then takes the square feet of the unit types (in this case we only have one type) and divides it by the total rentable square feet to get a square footage percentage. That percentage is then multiplied by the allocated water and sewer expense to get the unit calculated share (step 2). The investor must then calculate the occupancy portion of the equation by creating an occupant factor based on actual occupants and dividing it by the total combined occupant factor of the property. The result is the unit percentage which then needs to be multiplied by the allocated water and sewer expense to get the unit calculated share (step 3). Finally, the investor adds the square footage number for both expenses and adds it to the occupancy portion of the equation to get the total utility bill for the unit type (step 4).

With the final bill for the unit type we got in this example ($36.23), the investor would add that amount to the tenant’s rent and notify them that they are being billed for utilities. If the number of people living in their unit was to change at any point in time, their utility expense would fluctuate based on the new number of people living in that unit.

Key Principal

Key principals (KPs) are guarantors that provide either past experience, net worth, or liquidity to a deal. Whether a lender is offering a resource or non-recourse loan, they want to see someone on the sponsor’s team who helps mitigate the risk for the lender. In essence, KPs are involved in deals because they make up for the lack of either past experience, net worth, or liquidity which the sponsor(s) does not have. KPs can have a passive role in a deal or a more active one depending on what is agreed upon between the sponsor and the KP. Oftentimes KPs are compensated for what they bring to the table by getting a portion of the general partners/sponsor’s fees. Something that I should note is that the general rule of thumb when taking out a loan is that the sponsor group needs to have a combined net worth equal to 100% or more of the loan amount and 10% or more post-liquidity. Also, lenders will do background checks in addition to checking the personal financial statements (PFS) of the sponsor team and KP(s) who are backing the loan. One final thing I should note is that KPs are not necessary if the sponsor group meets the experience, net worth, and liquidity requirements the lender is looking for.

Step-Down

A step-down prepayment penalty is a predetermined sliding scale in which the amount of the penalty is based upon the principal balance of the loan in addition to how much time has passed. The most common scale for this prepayment penalty is 5%, 4%, 3%, 2%, 1%. For example, if an investor pays off a loan in the first year, they will have to pay a fee equal to 5% of the outstanding loan balance. If the investor pays off the loan in the second year, then they will have to pay 4% of the outstanding loan balance. This declining scale keeps repeating until the prepayment penalty no longer applies. Using the example from before, if the investor pays off the loan in year six, then they will not be hit with a prepayment penalty.

The pros of this prepayment structure are that it’s straightforward and easy to predict. In addition, it’s a good option in a declining or flat interest rate environment relative to yield maintenance and defeasance. A con is that some 10-year fixed-rate loans have prepayment penalties that start at 10% and decrease by 1% every consecutive year. That would make it difficult to pay off the loan in the early years and an investor might be better off with one of the other prepayment penalties. Another con is that this structure can be a poor choice in an environment where interest rates are rising.

Yield Maintenance

Yield maintenance is more difficult to understand then step-down, but in essence it’s designed to maintain the lender’s yield (aka their return on investment) throughout the fixed rate period of a loan. Before diving into the math, here’s how it works: in the event that rates have stayed flat or declined since an investor closes a loan, the lender profits on the present value of the difference between the interest rate on the loan and the current yield on the US treasury bond which most closely matches how many years the investor has left on their loan. Stated differently, if an investor gives back the lender their money prematurely, the investor will need to compensate the lender for the money they will lose having to invest in the lower return/yielding government bonds. If rates have risen to the point that yields the prepayment penalty negative/negligible, usually a 1% minimum will be charged to the investor.

The pros of this prepayment penalty are that if rates rise enough then an investor may only have to pay a 1% penalty which is reasonable. In addition, in a rising rate environment, an investor’s property may be worth more if the loan on the property is assumable. In other words, if interest rates are higher than that of the assumable loan, then an investor who assumes the loan will pay more for a property knowing their interest payments on the assumable loan will be less than that of market rate loans. A con is that if interest rates remain the same or decrease, an investor could be left with a high prepayment penalty.

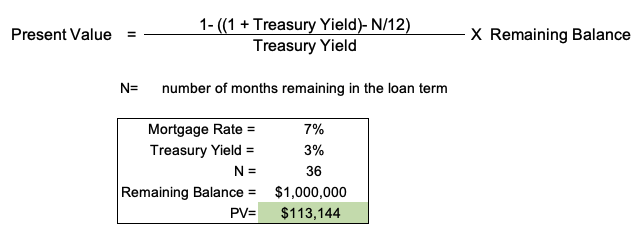

Consider this example, an investor wants to pay off their outstanding loan balance with three years (36 months) remaining in the repayment term. The investor was originally issued a 10-year loan at a 7% interest rate of which $1,000,000 is remaining. The investor goes on the U.S. Department of Treasury website and sees that the three-year treasury yield is 3% (notice how this investor has three years remaining on his loan and they take into account the three-year treasury in the calculation). The present value formula and math are shown in the illustration below. While I won’t explain all the mechanics behind this equation, we provide a yield maintenance calculator available for download on our website under the “education” tab.

Defeasance

Defeasance is the most difficult prepayment penalty to understand and requires several professionals including attorneys, a loan servicer, a third-party defeasance processor, and a bond rating agency or CPA’s to execute the process. In simple terms, a defeasance is the process of an investor taking the sale proceeds of a property to buy a security (usually a treasury bill) that matches the payment schedule of the loan that was paid off. The security would take the place of the payments that would have been made if the loan was never paid off in the first place. In a way, defeasance is similar to yield maintenance because the lender preserves their yield/return.

The cons to defeasance are that is it difficult to understand/calculate and also requires a cast of professionals in order to finish a transaction which adds additional costs. The pro is that in theory, it’s possible to pay off one’s loan at a discount if rates rise fast enough.

Conclusion

This post concludes the blog series I’ve been writing these past six weeks. I hope you’ve found these posts useful and continue to refer to them for as long as you need to. We’ve now covered over thirty terms if you take into account some of the extra terms sprinkled throughout the past posts. As noted above and in prior posts, a glossary section to the website is in the works. Also, I am building out several calculators to help make the math associated with some of the terms covered easier to understand and calculate. Once all of that is built, we’ll notify our followers via LinkedIn and Instagram. If you have any questions regarding the terms and concepts in this post or previous ones, don’t hesitate to reach out to either me (tedi.nati@jpacq.com) or someone on our team so we can help explain what is causing the confusion. If you’re interested in investing with us at JP Acquisitions, you can contact us via email, LinkedIn, Instagram, or our investor portal to set up a meeting. With the holidays approaching, on behalf of the team at JP Acquisitions we wish you and your family a safe and happy holiday!